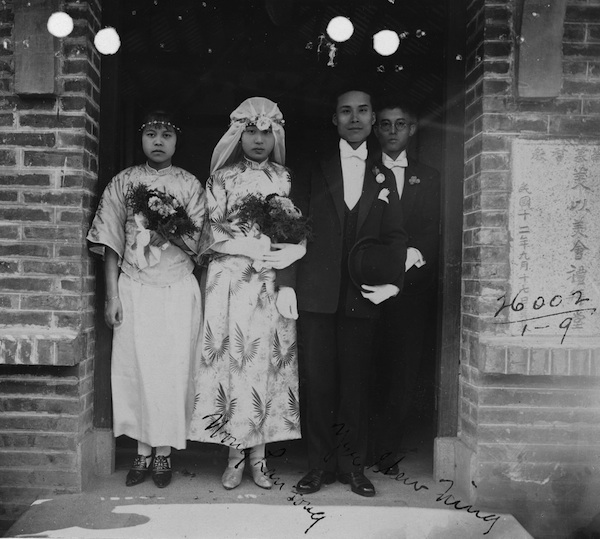

WASHINGTON — Wong Lan Fong brought her wedding picture with her when she came to America in 1927, but the photo of the 27-year-old bride was not a keepsake.

It was a proof to convince California’s immigration authorities that she did not come for “immoral purposes,” but to be reunited with her husband, a Chinese trader.

“They decided that it was important for them to arrive to the United States with a first-class ticket because they thought, rightly so, that the immigration officials would treat them better than if they came in steerage,” said Erika Lee, an immigration historian and Wong’s granddaughter.

Lee’s grandfather saved up for almost two years to buy the ticket, which allowed Wong to enter the country without prejudices faced by other Asian women. Wong’s slim file shows that her interrogation by immigration officials went smoothly.

Wong Lan Fong’s wedding picture is part of a new National Archives exhibit featuring the stories of 31 men, women and children who passed through U.S. entryways between the 1880s and the end of World War II.

The exhibit, called “Attachments: Faces and Stories from America’s Gates,” features mural-size black-and-white photos that were “attached” to immigration files. The original documents, letters and photos tell the stories of those who were entering, leaving or staying in the United States.

Exhibit curator Bruce Bustard said the exhibit illustrates the “long and complicated and contested history about immigration in the United States.”

Some of those entering were visitors; others came to America’s gates looking for freedom and prosperity for themselves and their descendants. Some brought a lot of money; others carried little. Some had their papers in order; others forged documents and had fake relatives sponsoring them.

These stories are drawn from millions of immigration cases on file at the National Archives. The exhibit is on display in the National Archives main building in Washington through Sept. 4. (Exhibition overview including its sections: Entering, Leaving and Staying)

One of the first pictures in the exhibit shows children arriving at Ellis Island in New York Harbor in 1908. The expressions on their faces show uncertainty, with some adults behind them smiling; others just stare at the camera.

Another view greeting visitors to the exhibit is a panoramic photo of Angel Island, the California processing facility that received half a million people, mostly Chinese and Japanese immigrants. It was built to be “the Ellis Island of the West,” but, under race-specific laws enacted in 1882, it also served as a detention facility, Lee said.

Like many other immigrants before and after them, some of the individuals featured in the exhibit could not enter America’s gates or were later sent home.

Among those featured are Rose and Emile Louis, an interracial couple coming from Britain. Emile was illiterate and was barred entry. Rose was denied entry as well, because her husband could not enter the country.

Pictures of six men deported because of “moral turpitude” listed their physical features to prevent them from re-entering. They include Dubas Wasyl, an Austrian farmhand who was caught stealing beans in his homeland and Francesco Zaccaro, who was sent back to Italy for “applying (a) vile name to a woman.”

“America’s gates have always swung in both directions,” said Joel Wurl, a senior program officer at the National Endowment for the Humanities, on a June 20 immigration panel at the National Archives. “Emigration also represents a part of the story.”

The exhibit also tells the stories of Mary Louise Pashgian, who came to the U.S. fleeing persecution in Armenia, or Kaoro Shiibashi, a Hawaiian raised in Japan who returned to his native land.

A picture of 13-year old Michael Pupa is attached to a file detailing how he hid for two years in the Polish forest after the Nazis murdered his parents. After living in many refugee camps, he came to the U.S. in 1951 and ended up living with a foster family in Cleveland.

“His story was one of many in the 25, 000 boxes of materials about children refugees after World War II,” Bustard said.

Pupa, the only person featured in the exhibit who is still living, visited the National Archives for the exhibit’s opening. Seeing his documents compelled him to share those experiences with his family for the first time, Bustard said.

In conjunction with the exhibit, the Archives also featured a series of events where experts discussed immigrant experiences at Angel Island, Ellis Island and other entry points, along with examples of global migration and exclusion.

“I love the original documents and the photographs,” said Quincey Johnson, a Maryland resident who was visiting the exhibit. “It’s a wonderful exhibit. It tells a number of really interesting stories about the difficulties people had.”

“It was interesting to see people from a number of countries, people who lost their families, people who were just trying to bring their families back together,” he told Catholic News Service.

— By Maria Pia Negro Catholic News Service