VATICAN CITY (CNS) — The Nativity story, like the whole story of Christ, is not merely an event in the past, but has unfolding significance for people today, with implications for such issues as the limits of political power and the purpose of human freedom, Pope Benedict writes in his third and final volume on the life and teachings of Jesus.

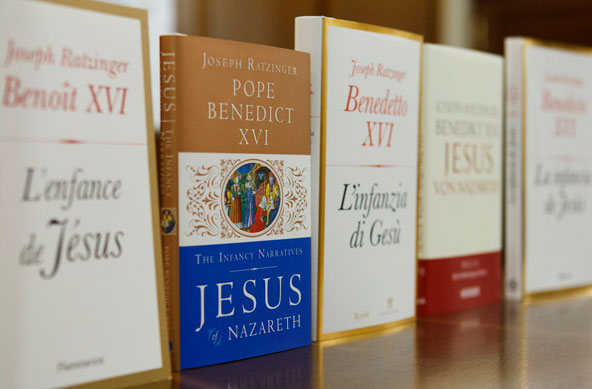

“Jesus of Nazareth: The Infancy Narratives” is only 132 pages long, yet it includes wide-ranging reflections on such matters as the significance of the Virgin Birth and the distinctive views of nature in ancient pagan and Judeo-Christian cultures.

The book was formally presented at the Vatican Nov. 20, and was scheduled for publication in English and eight other languages in 50 countries Nov. 21.

In the book, Pope Benedict examines Jesus’ birth and childhood as recounted in the Gospels of Sts. Matthew and Luke. His interpretation of the biblical texts refers frequently to the work of other scholars and draws on a variety of academic fields, including linguistics, political science, art history and the history of science.

The book’s publication completes the three-volume “Jesus of Nazareth” series, which also includes “From the Baptism in the Jordan to the Transfiguration” (2007) and “Holy Week: From the Entrance into Jerusalem to the Resurrection” (2011).

Jesuit Father Federico Lombardi, Vatican spokesman, said at the Nov. 20 book launch that the three books are the “fruit of a long inner journey” by Joseph Ratzinger, whose personal views they represent. While much of what the pope says is accepted Catholic dogma, the texts themselves are not part of the church’s Magisterium and their arguments are free to be disputed, Father Lombardi said.

In his new book, the pope argues that Matthew and Luke, in their Gospel accounts, set out to “write history, real history that had actually happened, admittedly interpreted and understood in the context of the word of God.”

The pope calls the virgin birth and the resurrection “cornerstones” of Christian faith, since they show God acting directly and decisively in the material world.

“These two moments are a scandal to the modern spirit,” which expects and allows God to act only in ideas, thoughts and the spiritual world, not the material, he writes. Yet it is not illogical or irrational to suppose that God possesses creative powers and power over matter, otherwise “then he is simply not God.”

The pope enriches the Gospel accounts with personal reflections as well as questions and challenges for his readers.

For example, considering the angel’s appearance to the shepherds, who then “went with haste” to meet the child Savior, the pope asked “How many Christians make haste today, where the things of God are concerned?”

Pope Benedict examines the political context of the time of Jesus’ birth, which featured both the so-called “Pax Romana” — the widespread peace brought by the Roman ruler Caesar Augustus — and King Herod’s thirst for power, which led to the slaughter of the innocents.

“Pax Christi is not necessarily opposed to Pax Augusti,” he writes. “Yet the peace of Christ surpasses the peace of Augustus as heaven surpasses earth.”

The political realm has “its own sphere of competence and responsibility;” it oversteps those bounds when it “claims divine status and divine attributes” and makes promises it cannot deliver.

The other extreme comes with forms of religious persecution when rulers “tolerate no other kingdom but their own,” he writes.

Any sign God announces “is given not for a specific political situation, but concerns the whole history of humanity,” he writes.

The pope writes that the Three Wise Men symbolize the purification of science, philosophy and rationality.

“They represent the inner dynamic of religion toward self-transcendence, which involves the search for truth, the search for the true God,” the pope writes.

The pope also argues that the star of Bethlehem was a true celestial event.

It “seems to be an established fact,” he writes, that the conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn happened in 7-6 B.C., which “as we have seen is now thought likely to have been when Jesus was born.”

A key topic in the book is the role of human freedom in God’s divine plan for humanity.

“The only way (God) can redeem man, who was created free, is by means of a free ‘yes’ to his will,” the pope writes. It is precisely “the moment of free, humble yet magnanimous obedience,” such as Mary and Joseph showed when listening to God, “in which the loftiest choice of human freedom is made.”

Jesus, too, in his human freedom, understood he was bound to obedience to his heavenly father, even at the cost of his earthly life.

The missing 12-year-old, rediscovered by an anxious Mary and Joseph in the Temple, was not there “as a rebel against his parents, but precisely as an obedient (son), acting out the same obedience that leads to the cross and the resurrection,” the pope writes.

Jesus’ birth, life, death and resurrection is a story filled with contradiction, paradox and mystery, the pope writes, and “remains a sign of contradiction today.”

“What proves Jesus to be the true sign of God is he takes upon himself the contradiction of God,” Pope Benedict writes, “he draws it to himself all the way to the contradiction of the cross.”

— By Carol Glatz and Francis X. Rocca, Catholic News Service