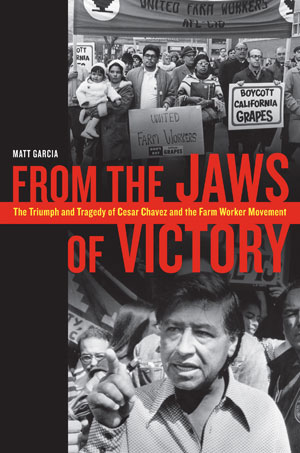

“From the Jaws of Victory: The Triumph and Tragedy of Cesar Chavez and the Farm Worker Movement” takes a critical look at Chavez and the rapid rise and fall of the United Farm Workers agricultural union he guided.

Labor historian Matt Garcia defends his assessment as a search for “usable knowledge” for future organizing, and a way to “hold the UFW leadership accountable to the thousands of farmworkers who were let down by the union’s retreat from the fields.”

In 1960, there was no union for California grape pickers. By 1970, fully 12,000 were members of the UFW, Garcia reports. “From the Jaws of Victory” concludes with this sobering fact: “Today not one field worker laboring on grape farms in California is covered by a labor contract.”

What happened? Garcia uses written accounts and oral interviews with organizers to answer this question. The responses include open criticism of Chavez, a man many Mexican-Americans and Catholics claim as their own American hero.

Chavez died in 1993 at the age of 66. His birthday, March 31, has been declared a state holiday in eight states. A champion of nonviolence, his organizing techniques used church practices such as fasting and pilgrimage. His vision attracted educated, white volunteers, many from church backgrounds.

Garcia writes that “obstinacy” and “willingness to risk everything” were “hallmarks of Chavez’s leadership.” They helped him build a movement and they played a part in its collapse.

Those curious about criticism of Chavez will turn directly to the chapters that focus on these disintegrating years of the mid-1970s when the charismatic leader veered to autocratic, cultlike behavior.

In those years Chavez founded La Paz, a communal living experiment, and centered union offices there. The UFW turned from direct union organizing to passing legislation and a funding referendum. After huge investments of time and money, the referendum failed in 1976. Chavez “took the defeat personally” and “became erratic,” Garcia writes.

Chavez fell under the influence of Synanon, a residential community for drug rehabilitation that used a direct confrontation technique it called the “Game” as a way of correcting member behavior.

Chavez brought the Game to La Paz and the UFW. Former members and allies “tried to point out the violence inherent in the words and threats that flowed from the Game,” Garcia writes. “Chavez dismissed the concerns as further evidence of agents conspiring to bring down the union.”

Garcia says that the Game changed the UFW from a multiethnic, multigenerational, multiclass movement to one where only young, Mexican laborers were welcome as leaders. The union developed two cultures: “obedience to Chavez at the La Paz headquarters, and resistance and nonconformity away from it.” Shared communal purpose devolved into harassment, character assassination and ideological purges.

The movement was also weakened by ethnic divisions, intra-union fights, and diversion of efforts from organizing workers to supporting ballot initiatives.

Garcia says that the story of the UFW is particularly relevant now, “at a time when the new food justice movement is on the rise.” The UFW used the internationally successful grape boycott of 1966-70 to make agricultural conditions a social justice issue. The boycott mustered support of urban consumers who were far removed from farm life. The new food justice movement can learn from the successes and failures recounted in “From the Jaws of Victory.”

– – –

— Reviewed by Maureen Daly Catholic News Service. Daly, writing from Baltimore, has worked with faith-based community organizing on employment issues since 2008.