VATICAN CITY (CNS) — The voting by cardinals to elect the next pope takes place behind the locked doors of the Sistine Chapel, following a highly detailed procedure that underwent major revisions by Blessed John Paul II and a small, but very significant change, by Pope Benedict XVI.

Under the rules, secret ballots can be cast once on the first day of the conclave, then normally twice during each subsequent morning and evening session. Except for periodic pauses, the voting continues until a new pontiff is elected with at least two-thirds of the votes.

Bishop Juan Ignacio Arrieta, secretary of the Pontifical Council for Legislative Texts, reviewed the rules with reporters at the Vatican Feb. 22.

Introducing Bishop Arrieta, Jesuit Father Federico Lombardi, the Vatican spokesman, said Pope Benedict at any minute might be signing a document with minor changes to the law, but the changes would make sense only if one knew the general laws for a conclave.

Many observers had expected Pope Benedict to clarify that the cardinals have the option of beginning the conclave once all the cardinals are in Rome, even if that occurs sooner than the law’s required 15 days after the beginning of the “sede vacante,” literally the vacant see, left by the pope’s resignation.

Bishop Arrieta told reporters that in his opinion the cardinals could make that decision on their own, without a change to the law, since the law was “clearly written with a ‘sede vacante’ because of death in mind.” However, he also said that as the church’s supreme legislator, Pope Benedict, before leaving, also could set the date for the conclave, “although I have no information that he would do so.”

The written rules for the conclave, which have developed in reaction to the problems — political and moral — that have arisen throughout history, are “rigid and highly formal,” the bishop said.

For example, he said, Pope Paul VI’s rules excluded cardinals who were 80 years old or older on the day the conclave began. Blessed John Paul changed the rule to 80 years on the day the papacy became vacant. The change ensured cardinals did not choose a conclave start date specifically to include or exclude a cardinal close to the age of 80.

Under current rules, only cardinals who are under the age of 80 Feb. 28, the last day of Pope Benedict’s pontificate — can vote in the conclave. There were 117 cardinals eligible, but Feb. 21 Indonesian Cardinal Julius Darmaatmadja, the 78-year-old retired archbishop of Jakarta, announced he would not travel to Rome because of his health.

In theory, any baptized male Catholic can be elected pope, but current church law says he must become a bishop before taking office; since the 15th century, the electors always have chosen a fellow cardinal.

Each vote begins with the preparation and distribution of paper ballots by two masters of ceremonies, who are among a handful of noncardinals allowed into the chapel at the start of the session.

Then the names of nine voting cardinals are chosen at random: three to serve as “scrutineers,” or voting judges; three to collect the votes of any sick cardinals who remain in their quarters at the Domus Sanctae Marthae; and three “revisers” who check the work of the scrutineers.

The paper ballot is rectangular. On the top half is printed the Latin phrase “Eligo in Summum Pontificem” (“I elect as the most high pontiff”), and the lower half is blank for the writing of the name of the person chosen.

After all of the noncardinals have left the chapel, the cardinals fill out their ballots secretly, legibly and fold them twice. Meanwhile, any ballots from sick cardinals are collected and brought back to the chapel.

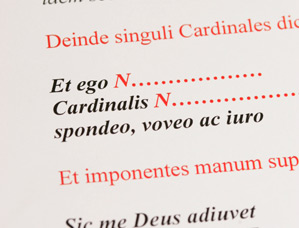

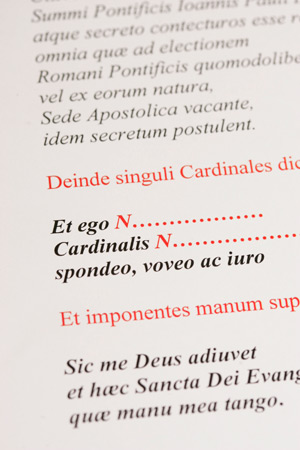

Each cardinal then walks to the altar, holding up his folded ballot so it can be seen, and says aloud: “I call as my witness Christ the Lord who will be my judge, that my vote is given to the one who before God I think should be elected.” He places his ballot on a plate, or paten, then slides it into an urn or large chalice.

When all of the ballots have been cast, the first scrutineer shakes the urn to mix them. He then transfers the ballots to a new urn, counting them to make sure they correspond to the number of electors.

The ballots are read out. Each of the three scrutineers examines each ballot one-by-one, with the last scrutineer calling out the name on the ballot, so all the cardinals can record the tally. The last scrutineer pierces each ballot with a needle through the word “Eligo” and places it on a thread, so they can be secured.

After the names have been read out, the votes are counted to see if someone has obtained the two-thirds majority needed for election. The revisers then double-check the work of the scrutineers for possible mistakes.

At this point, any handwritten notes made by the cardinals during the vote are collected for burning with the ballots. If the first vote of the morning or evening session is inconclusive, a second vote normally follows immediately, and the ballots from both votes are burned together at the end.

When a pope is elected, the ballots are burned immediately. The ballots are burned with chemical additives to produce white smoke when a pope has been elected; they are burned with other chemicals to produce black smoke when the voting has been inconclusive.

The conclave is organized in blocks: three days of voting, then a pause of up to one day, followed by seven ballots and a pause, then seven more ballots and a pause, and seven more ballots.

Slightly changing the rules in 2007, Pope Benedict said that after about 33 or 34 ballots without an election — about 12 or 13 days into the conclave — the cardinals must move to a run-off between the top two vote-getters. The two candidates may not participate in the voting, Bishop Arrieta said, and one of them is elected only once he obtains more than two-thirds of the vote.

— By Cindy Wooden Catholic News Service