The war in Vietnam was still smoldering and the Supreme Court had not yet legalized abortion when Margaret Saunders Moan first waded into the abortion controversy.

One of nine daughters, many of whom became outspoken critics of abortion, Margaret Moan was on the cusp of a budding local pro-life movement whose members eventually became social workers, attorneys, deacons, teachers, psychologists, adoptive parents and journalists. Between them they have dozens of children, many of whom continue to carry the pro-life torch.

“I was taking a speech class at Phoenix College,” Moan said. “I was the only one who was on the pro-life side of the debate.”

The professor interrupted Moan’s speech repeatedly to interject her own views and ultimately gave her an “F” on the assignment.

“She was obviously pro-abortion,” Gene Moan, Margaret’s husband, recalled about the incident. “She offered to let Margaret redo the assignment by defending the opposite position.”

“I told her I couldn’t do that and picked another topic,” Margaret said. “Her attitude spurred me to want to know more.”

Margaret dug in deep at the Arizona State University library — this was the era before internet Internet search engines — and wound up co-founding Arizona Youth for Life, an energetic coalition of high school and college age students dedicated to taking the abortion issue to the streets. AYFL, frequently in the spotlight via local newspapers and television, thrived at Catholic and public high schools in the Diocese of Phoenix, as well as on local college campuses. With a speakers’ bureau, weekly protests at abortion clinics, a booth at the state fair, political activism and civil disobedience, the group was a force to be reckoned with.

Speaking out

Eileen, Margaret’s sister, was an ASU student when she got into a debate about abortion with a classmate by the name of Matt Berens who was studying business. Though he considered himself pro-life in high school, by the time he got to college he said he’d fallen prey to pro-abortion slogans.

“I admitted I lost the debate after about five minutes,” Berens said. “It was hard to fight the facts. Slogans are cheap and they don’t have a lot to them.”

Matt began dating Eileen — the two eventually married, becoming lawyers — and attended an AYFL meeting at the Moan’s apartment. With his business school training, Matt created an action and marketing plan for the group.

“The early response to Roe v. Wade had been somewhat muted,” Matt said. Arizonans were by and large conservative and opposed to the Supreme Court’s decision, he said, but they weren’t out in the streets protesting it. Many believed there had to be a political solution and young people were often relegated to stuffing envelopes.

For teenagers and twenty-somethings loaded with energy and fueled by idealism, it wasn’t enough.

“We were trying to keep the issue in front of the public,” Matt said. “We were the ones who did the picketing, sidewalk counseling and a number of our group became the ones who did the sit-ins.”

The Moans organized a speakers’ bureau that trained young people to speak out on abortion. Liz Saunders was in charge of the AYFL newsletter that had a mailing list of over 1,000. The group was given free office space in the U-Haul tower on Central Avenue.

Ellen Sweeney was a freshman at St. Mary’s High School when she got involved.

“I went to an AYFL meeting. Abortion had just been legalized,” Sweeney said. “I just could not believe it was legal. It was insane.”

Sweeney underwent intensive training to become a speaker for AYFL, giving presentations in classes at ASU and public schools around the Valley.

“I remember thinking, ‘I’m 14. Who’s going to listen to me?’” Sweeney said. She spoke to her uncle, a priest, who quoted Jeremiah. “Say not I am too young. To whomever I send you, you shall go,” he told her.

“It’s kind of like we were so young we didn’t know what we couldn’t do,” Sweeney said. “It’s amazing to me to look back at the scope of the things we did.”

That included defending the pro-life position in debates against adults or when reporters covered protests such as the three-day hunger strike over Thanksgiving weekend in 1979. AYFL members camped out in front of the Federal Building in downtown Phoenix for three days. While others feasted, they ate nothing.

All agreed that there was a sense of urgency during those early days of the pro-life movement.

“We have to do something,” Sweeney remembered thinking at the time. “It was the idealism and confidence of youth. We thought that we, the young people, would be able to change it.”

Sweeney said it’s hard to believe 41 years have passed since those early days. She remains active in the cause through the 40 Days for Life campaigns.

Courageous efforts

John Jakubczyk grew up in Scottsdale and was a freshman in college at the University of San Diego when the Roe v. Wade decision came down. He eventually got involved in AYFL and went on to become president of Arizona Right to Life.

The father of 11 remembers when several members of AYFL began participating in sit-ins at local abortion clinics, long before the advent of Operation Rescue.

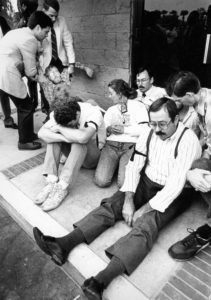

Sweeney, her sister Bridget, and several others entered an abortion clinic on south Seventh Avenue in Phoenix in 1980 and chained themselves to one of the examining tables. Outside the clinic, dozens of picketers marched with signs. The story topped the evening news and made the front page of The Arizona Republic. The trial several months later grabbed headlines.

The civil disobedience at clinics around Phoenix continued and Jakubczyk at one point defended some of the protestors in court.

Sweeney’s sister, Bridget Martin, one of the arrestees who was active in the AYFL speakers’ bureau, is a kindergarten teacher at St. Francis Xavier Catholic School.

“We were essentially in a war,” Martin said. “We were forged in fire. I think it surprises anyone to find out I was arrested, but I don’t think it surprises them much.”

Like the other activists of that era, she said she wouldn’t be the person she is today without early formation in the pro-life movement. The fire of those early years has been tempered by experience and by love, she said.

“I think we have a great foundation in love in AYFL,” Martin said. “All those protests, the hunger strike — they were bonding experiences.”

Many of the pioneers say they believed as young people that it was a matter of convincing people that the unborn were human beings who deserved protection.

The history of law in America, Matt said, has been that of extending protection to more and more people, not the other way around.

“It’s just a sheer turning away from the facts of what is in front of you to come up with justification for abortion,” Matt said. “People say, ‘It’s a human being. So what?’ If that doesn’t get you the protection of the law, you scare the hell out of me.”