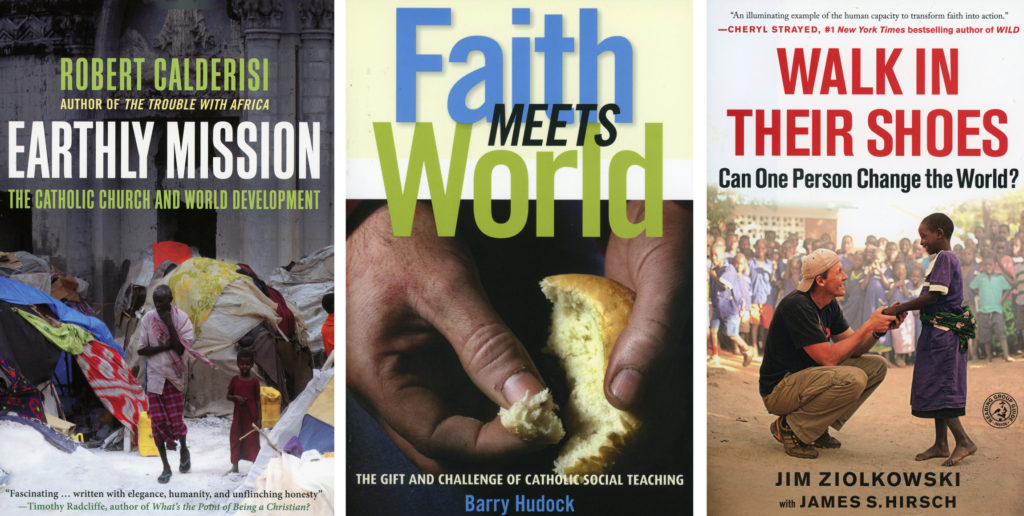

Readers interested in the Catholic Church’s role in international development will benefit from reading “Faith Meets World: The Gifts and Challenge of Catholic Social Teaching” by Barry Hudock, “Walk in Their Shoes: Can One Person Change the World?” by Jim Ziolkowski with James S. Hirsch, and “Earthly Mission: The Catholic Church and World Development” by Robert Calderisi.

The books explain that the church long has been a formal presence in international development and that individuals rooted in Catholic tradition, prayer and Catholic social teaching can change the world.

But fair warning: Readers might feel inspired and uncomfortably challenged while reading these books, for answering the call of Catholic social teaching, the books point out, is not an easy task.

Hudock explains this last point best in “Faith Meets World.” Catholic social teaching, based on the two principles of human dignity and solidarity, encourages Catholics to be with and live among the poor and destitute. One must see the image of God in everyone: the oppressor and oppressed, those born and unborn.

These are not new concepts to the church, and have been realized and expanded since Pope Leo XIII’s 1891 encyclical “Rerum Novarum” (on capital and labor), a response to the Industrial Revolution and document in support of just conditions for workers. Blessed John XXIII not only addressed human rights in 1963 with “Peace on Earth” (“Pacem in Terris”), Hudock writes, the pope also directly intervened in successfully ending the Cuban missile crisis. The list of official contributions to Catholic social teaching goes on and on.

Without being wordy or dense, Hudock clearly marries the historical background of Catholic social teaching to its practical application into society. To illustrate his points, he addresses modern-day affronts to human rights in Vietnam and Syria, and highlights Cesar Chavez and Dorothy Day as true champions of solidarity and human dignity.

Ziolkowski could make an appearance in Hudock’s book as an example of living out Catholic social teaching. “Walk in Their Shoes” tells the story of Ziolkowski’s journey from comfortably working in corporate America to sleeping on dirt floors in Malawi. Upon returning from a backpacking trip in India, Thailand and Nepal, Ziolkowski could not shake the images of poverty that he saw. He could have ignored it all — like what Albert Schweitzer in “Reverence for Life” called falling victim to a “sleeping sickness of the soul.” But Ziolkowski felt a call to action.

So he quit his finance job and created buildOn, a nonprofit foundation that links at-risk American high-schoolers with service projects to help build community leadership at home and build schools abroad. Ziolkowski’s idea to break the cycle of poverty is unique. Students and villagers volunteer their time as dedicated stakeholders in the projects’ success. And because of this very investment of time and passion, the projects come to fruition.

“Walk in Their Shoes” is not another “Three Cups of Tea,” the now-questioned memoir by Greg Mortenson and David Oliver Relin. “Walk in Their Shoes” is hard to put down and hard to forget once finished. Ziolkowski writes like a good friend, sharing stories about his family, particularly his father, a strong force of faith in his life, and his young son, whose illness forced Ziolkowski to face true suffering.

Unlike “When Faith Meets World” and “Walk in Their Shoes,” “Earthly Mission” covers the church’s work in developing countries broadly and extensively.

In an effort to be balanced and thorough in his assessment of the church’s involvement in Africa, Asia and Latin America, Calderisi, an economist with 30 years of experience in international development, takes an in-depth approach at tackling a broad range of topics. He discusses church history, social teaching, the church’s action — and inaction — in the 1994 Rwandan genocide, contraceptives and population control, as well as the church’s role in Africa, Asia and Latin America. It’s a lot to handle, and at times, a lot to digest.

Calderisi notes individual Catholics’ good work in developing countries. He gives credit to the formal and traditional institutions of the church, including the very presence and global reach of the church that set up the framework for individual Catholics to do good work.

He concludes that the church’s work in education and health has been life-saving for the poor, particularly women. But he also points out the church’s bleak moments: what he sees as its gross negligence and outright compliance in the Rwandan genocide, and its need to maintain its identity and self-preservation sometimes at the hindrance of those working on the ground.

As these three books each address in their own way, it is up to individual Catholics to carry out social teaching.

And so the uncomfortable question lingers: Will the reader honor the call to work toward human dignity and solidarity at home and abroad or will he or she fall victim to the sleeping sickness of the soul?

— Reviewed by Regina Lordan, Catholic News Service. Lordan is a former assistant international editor of Catholic News Service.