WASHINGTON (CNS) — People don’t seem to count gains and setbacks on the death penalty issue with quite the same intensity as they do with other issues. Even so, slowly but surely, gains are being made — and more gains than setbacks.

Even the setbacks can, ironically, be counted as gains.

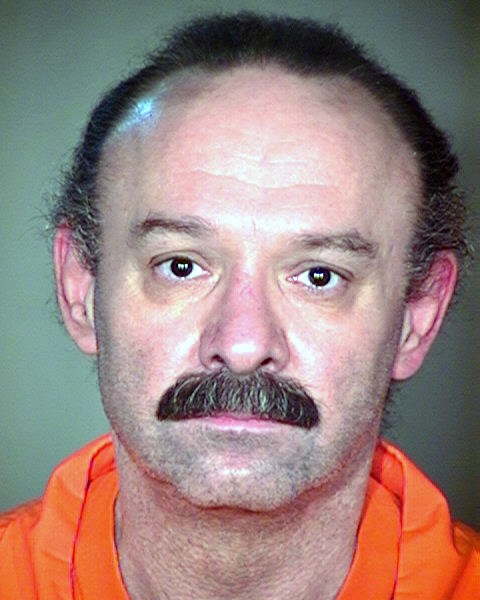

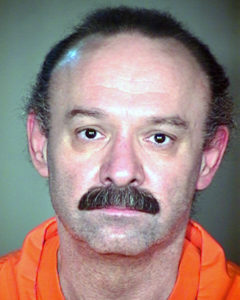

One notable case in point is the July 23 execution of Joseph Wood in Arizona. Wood’s attorneys had briefly won a temporary blockage of his execution by demanding to know what kinds of drugs were planned for use by the state in the death chamber.

The state successfully challenged the stay and Wood, convicted of two 1989 murders, was executed according to schedule, but hardly according to plan.

After the drug cocktail was injected in him, it took an hour and 57 minutes for Wood to die. Although a relative of one of the victims witnessing the execution said Wood was snoring, others witnessing the scene said Wood was gasping. Wood’s lawyers tried, albeit without success, to get the Supreme Court to order the state to halt the execution process as it was taking place, calling it cruel and unusual punishment. Arizona ultimately called for a review of the process.

The Wood case echoed that of an Oklahoma death-row prisoner, Clayton Lockett, who writhed in agony for 40 minutes before being unhooked from the drug dispenser in the death chamber. Lockett soon died of apparent heart failure. The incident prompted Oklahoma officials to review its execution procedures. Oklahoma recently moved ahead of Virginia, taking second place in a list of the states with the most executions; Texas is still in first place. Arizona has said it also will review its procedures.

Death penalty opponents have already made headway with physicians, almost all of whom now will refuse to assist at an execution. Opponents’ next step is getting pharmacists and pharmaceutical companies to stop supplying the drugs used in lethal injections, saying drugs should be used for healing, not for killing.

States have fought efforts like those made by Wood’s attorneys to keep the drugs and their sources secret, claiming suppliers will be harassed and intimidated.

Even so, the initial Arizona ruling “was full of nuance — getting in to the moral aspect of it,” said Karen Clifton, executive director of the Catholic Mobilizing Network Against the Death Penalty. “The practice is just cruel and unusual. … It goes against our Constitution as cruel and unusual punishment. I hope there is another judge in another state that has a conscience and will make similar ruling on it.”

Richard Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, noted the “slow erosion of support” for capital punishment in public-opinion polls.

A Gallup poll question registered 80 percent support for capital punishment in 1994. “That has dropped to 60 percent very recently — the same Gallup poll, the same question,” Dieter said.

He also cited an ABC News-Washington Post poll showing more respondents choosing life without parole over the death penalty for convicted murderers when given the choice.

Catholics “used to be right up there” with the rest of the country in their support for capital punishment, Dieter said. Now, “they are more opposed to the death penalty than the average among voters. In some polls, they appear to be against the death penalty,” he added.

The U.S. bishops, who have long advocated against capital punishment, began an ongoing Catholic Campaign to End the Use of the Death Penalty in 2005.

One long-held argument for capital punishment was that “it’s an essential part of the criminal system,” Dieter told Catholic News Service. It’s ceased being part of that, if it ever was. … It’s a marker rather than an essential element that people feel in some personal way. And courts are a little reluctant to get too far ahead, lest they do wrong in reading the public opinion.”

The Catholic Church has taught clearly that while the death penalty might be allowed if it were the only way to protect society against an aggressor, those cases, according to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, are “very rare if practically nonexistent.”

One big test of public opinion is likely to come in 2016, when Californians will vote on a referendum, the Death Penalty Reform and Savings Act, that could abolish the death penalty in the nation’s most populous state.

The last execution in California was in 2006. Later that year, a federal judge imposed a moratorium on executions in California, which has continued to this day. A 2011 study said the state had spent $4 billion trying capital cases. On July 16, another federal judge declared the state’s death penalty unconstitutional, saying it was arbitrary and plagued with delay.

A 2012 referendum that would have abolished capital punishment in the Golden State was rejected by a 52 percent to 48 percent margin.

California falls into a significant group of states with a death penalty still on the books, but with no executions in recent years. A half-dozen states have only executed prisoners who said they wanted to be put to death for their crimes. In other states, governors or courts have imposed moratoriums on capital punishment.

“The judges are now starting to look at the states that now have moratoriums as repeal states,” said Clifton of the Catholic Mobilizing Network. Eighteen states have banned capital punishment, she added, but “the numbers are far greater … when you factor in all these states have a moratorium.”

Another point that could give pause to advocates on either side of the issue is the revelation in 2012 that a FBI forensics lab committed errors in hair matches in cases throughout the 1980s and 1990s. On July 22, a District of Columbia man was freed after 26 years in prison for a 1982 murder because of the FBI lab’s errors.

While D.C. has no death penalty, other states do. “We can’t say anymore that we’ve never sent an innocent person to their death,” Clifton told CNS. “No one can.”

— By Mark Pattison, Catholic News Service.