SELMA, Ala. (CNS) — The message of the civil rights movement has always been that all people are created in the image and likeness of God and that the dignity of all must be respected, said Mobile Archbishop Thomas J. Rodi.

He was the main celebrant and homilist at a Mass March 8 at Queen of Peace Church in Selma marking the 50th anniversary of the 1965 civil rights marches from Selma to Montgomery.

Respect for the dignity of all remains the challenge for today, Archbishop Rodi said, adding that he wondered what the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who led the marches and was “first and foremost a religious leader,” would think about things today.

“Do we respect the dignity of the elderly, the immigrant, the baby in womb? That continues to be the struggle for each of us,” Archbishop Rodi said in a homily that described the Catholic Church’s persistent presence in addressing both the spiritual and temporal needs of God’s people.

He said that the media often leave out “Rev.” in describing the civil rights giant, and in doing so they are omitting the spiritual and primary vehicle that carried his nonviolent quest forward — one anchored in the dignity of the human person.

Concelebrants included three of the nation’s African-American Catholic bishops:

- Louisiana Bishop Shelton J. Fabre of Houma-Thibodaux

- Washington Auxiliary Bishop Martin D. Holley

- retired Bishop John H. Ricard of Pensacola-Tallahassee, Florida

Others who concelebrated were Edmundite Fr. Stephen Hornat, superior general of the Society of St. Edmund; Edmundite Father Richard Myhalyk, pastor of Queen of Peace; Fr. James Curran from the Diocese of Richmond, Virginia; and Fr. Thomas Weise, retired pastor of St. Patrick Parish in Phenix City, Alabama, and a longtime civil rights advocate.

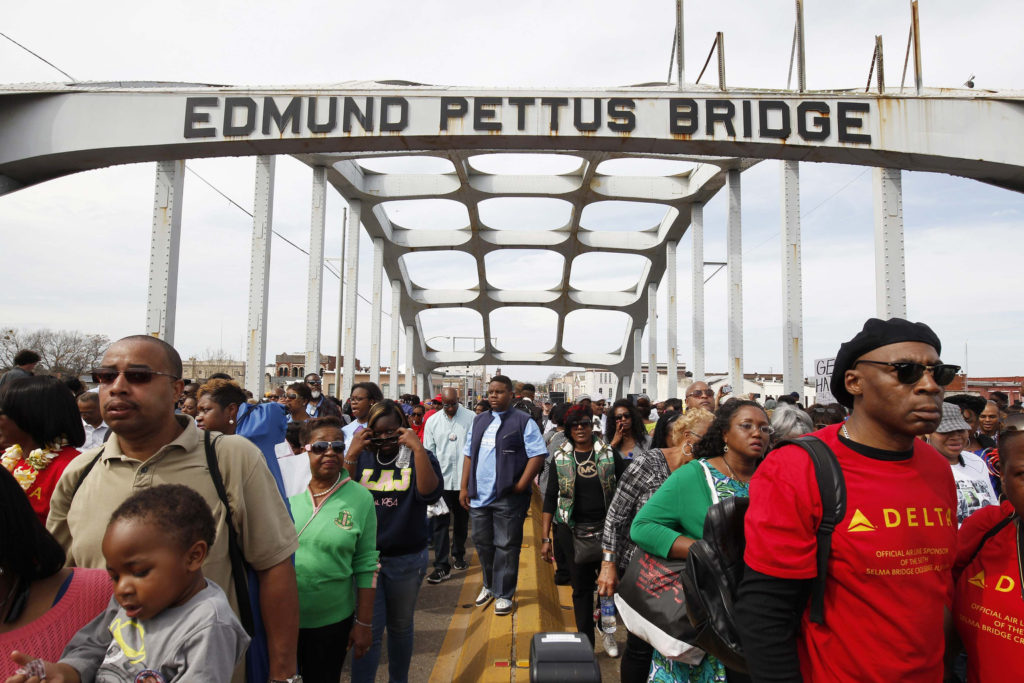

On March 7, 1965, a young Alabaman named John Lewis — now a veteran congressman representing Georgia’s 5th District — and other local civil rights activists led about 600 marchers in a peaceful procession from Selma across the Edmund Pettus Bridge toward Montgomery.

[quote_box_right]

Related

African American Catholics in the U.S. (USCCB)

‘Selma’ prompts painful memories for Sister of St. Joseph who marched (Catholic News Service)

Illinois bishop on racial divide in the U.S.

Sr. Ebo, an icon during the struggle for voting rights

[/quote_box_right]

They risked imprisonment and injury to protest infringement of voting rights against African-Americans in Selma and the brutal murder of a demonstrator by a state trooper a month earlier. March 7 came to be known as “Bloody Sunday,” as police — some on horseback — released tear gas and beat some of the marchers over the heads with truncheons.

The Rev. Martin Luther King led the second march, which took place March 9, 1965. He galvanized more than 2,000 people to participate. They included ministers, priests, nuns and rabbis around the country who answered a call to join him. Through newspaper accounts and television coverage, the world saw blacks and whites, men and women, clergy of all faiths, Catholic priests and nuns, walking arm-in-arm.

But Rev. King turned the march back at the bridge, after time spent in prayer. He did so at the urging of members of Congress who wanted federal protection for the demonstrators but had not yet secured it. A third march started from Selma March 21, 1965, with federal protection for participants. Walking between seven and 17 miles a day, and camping along the way, the marchers reached the steps of the Capitol in Montgomery March 25, 1965. The crowd grew to 25,000 on the last day.

On Aug. 6, 1965, the federal Voting Rights Act was passed and it was signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson.

This year on March 7 in Selma, a crowd of about 40,000 watched as President Barack Obama, first lady Michelle Obama and the couple’s two daughters were joined by U.S. Rep. Lewis, D-Georgia and a few others in a symbolic walk across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. For security reasons, the crowd could not walk on the bridge with the president.

More than 100 members of Congress were in attendance, as was former President George W. Bush, who signed the reauthorization of the Voting Rights Act in 2006.

“The march on Selma was part of a broader campaign that spanned generations, the leaders that day part of a long line of heroes,” Obama said in his remarks.

“We gather here to celebrate them. We gather here to honor the courage of ordinary Americans willing to endure billy clubs and the chastening rod; tear gas and the trampling hoof; men and women who despite the gush of blood and splintered bone would stay true to their North Star and keep marching toward justice,” he said.

“The Americans who crossed this bridge, they were not physically imposing. But they gave courage to millions,” said Obama. “They held no elected office. But they led a nation. They marched as Americans who had endured hundreds of years of brutal violence, countless daily indignities — but they didn’t seek special treatment, just the equal treatment promised to them almost a century before.”

Selma is not “some outlier in the American experience,” or a museum, or “a static monument to behold from a distance,” he said. “It is instead the manifestation of a creed written into our founding documents” that “all men are created equal.”

He said the racial unrest and rioting in Ferguson, Missouri, that followed the fatal shooting of a black teenager by a white police officer last August “may not be unique, but it’s no longer endemic (and) no longer sanctioned by law or custom,” as it was before the civil rights movement, he said.

At the same time, however, Ferguson is not “an isolated incident” and racism in the U.S. has not been “banished,” Obama said, adding that no one needs the Justice Department’s newly released report on racism in the Ferguson Police Department to know that racism has not been defeated.

“We just need to open our eyes and our ears and our hearts to know that this nation’s racial history still casts its long shadow upon us. We know the march is not yet over; we know the race is not yet won,” said Obama.

In Selma in 1965, Rev. King told John Wright Jr., a correspondent for the National Catholic News Service, as it was called then, that the presence of Catholic priests and nuns at the march “has given a new, creative and encouraging dimension to our whole struggle. It has identified the church with the struggle in a way that has not existed before.”

In one of his several reports filed back to the news service in Washington, Wright said Rev. King was deeply moved by the role priests and nuns played in the Selma march.

“(Rev. King) believes that the presence of the priests and nuns in Selma had a direct effect on the swiftness of President Johnson’s actions in recommending extensive voting laws to Congress,” Wright wrote.

Contributing to this story was Larry Wahl, editor of The Catholic Week, newspaper of the Archdiocese of Mobile.