SACRAMENTO, Calif. (CNS) — It’s difficult to miss the mark that the missions have had on the Golden State. Evidence of their influence is seen in places and people throughout California.

The missions provided the “beginnings of who we are today” as Californians, said Franciscan Father Ken Laverone, who is five generations removed from a Spanish soldier assigned to the pueblo of San Juan Bautista.

“I was baptized in the mission,” he said. “I made my first Communion there. I was ordained a priest there. All my family has been buried there, so it’s home for us.

“Most of California as we know it — names of cities, mountains, rivers — they all came from (Blessed Junipero) Serra, the Spanish and the missionaries. So our heritage in a sense, our patrimony in terms of our identity, comes from that.”

Father Laverone, who is a co-postulator in Blessed Junipero’s sainthood cause, admits that not all of the results were good.

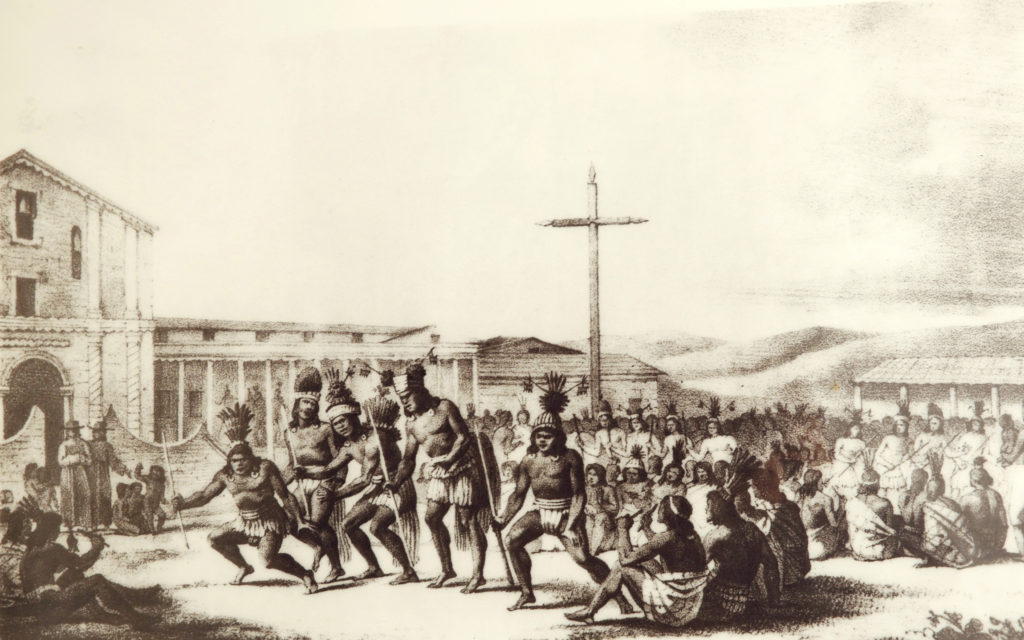

“Obviously, the colonization and the effects of colonization brought terrible tragedy into the native country,” he told Catholic News Service.

Spanish colonization, European diseases that ran rampant in missions and the gold rush, during which Indians were enslaved and killed, nearly eradicated California Indian populations.

California mission history is so profound that it has been required study for all fourth-graders in the state. On mission field trips, students find museum displays, artwork and old artifacts, but also parishes that are very much alive.

“I think some people are surprised by that,” said Father Tom Elewaut, pastor of San Buenaventura Mission in Ventura.

Today, all but two of the 21 historical missions are active churches, and most of those are parishes that continue to serve local communities.

“We have 1,800 active parishioners that attend, participate in Sunday worship,” said Father Elewaut, adding that at every Mass there also are people visiting from across the United States, Canada, Europe or other parts of the world.

Father Elewaut estimates that about half of his parish is Latino. Some families have been with the parish for generations, including the Ortega family, who began the Ortega Chile Packing Co. about three blocks from the mission. It was among the first commercial food operations in the state.

The priest said mission parishes have a unique responsibility to be caretakers of history and mission outreach.

“There’s a certain reverence from the parishioners to preserve the legacy and the spiritual center that has been entrusted to us, to continue to evangelize today.”

San Gabriel Mission is considered the mother church of Los Angeles, a city which is the seat of the largest Catholic archdiocese in the country in terms of Catholic population.

Xavier Vargas and his family are longtime parishioners of San Gabriel. His children and grandchildren were all baptized in the mission, some with the same silver shell used by its first missionaries.

He said he has a high regard for the missions and Blessed Junipero, whom he views as an intelligent, hard-working man who helped educate as well as evangelize native Californians.

When asked what intercession he might pray for from the soon-to-be St. Junipero, Vargas is quick to answer.

“Keep our missions going. Definitely keep our missions going, because there’s a great deal of pride and also a lot of history here that people don’t realize and we take for granted.”

Pope Francis will canonize Blessed Junipero Sept. 23 in Washington. The friar was beatified in 1988 by St. John Paul II.

Many people point to the missions for planting the seeds that eventually grew into California’s multibillion-dollar agricultural industry.

The Franciscans taught Indians to plant and harvest Spanish wine grapes, oranges, almonds, olive trees and other produce. From Mexico the padres brought grazing animals. Today, California remains a top producer of dairy products, almonds and grapes.

A large number of people populating the pews of the missions today are immigrants and the descendants of immigrants from Mexico who came to work California ranches and fields.

Caretakers at Mission Soledad still tend a small grove of Spanish olive trees and sells oil pressed from its fruit in the mission’s tiny gift shop.

Two missions, La Purisima Concepcion in Lompoc and San Francisco Solano in Sonoma, are state parks with exhibits detailing early life of the missions, and the periods of secularization and abandonment and also restoration and revival.

Other missions are parishes as well as centers of city life.

Outside Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa, where its steps lead to San Luis Obispo’s Mission Plaza, people often congregate for festivals and concerts.

In the seaside city of Carmel, San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo Mission hosts a popular classic auto show and festival that draws people from across the county. The Carmel Mission Classic held in August benefits mission restoration efforts and Knights of Columbus charities and includes a “blessing of the cars.”

As tourists wander Carmel mission taking in its beauty and history and getting a glimpse of the final resting place of Blessed Junipero, they often interact with parishioners or typical parish activities like first Communion services and pancake breakfasts.

In Southern California, Mission San Juan Capistrano attracts tens of thousands of students and visitors each year. Its Serra Chapel from 1782 is the oldest extant building in California and the only remaining church where Blessed Serra celebrated Mass.

On the campus of Santa Clara University in California’s Silicon Valley, sits Mission Santa Clara de Asis. The Jesuit university has the distinction of being the first institution of high learning in the state as well as the only California college to be the successor of a Spanish mission. Students, faculty and alumni often celebrate their marriages in the finely restored mission church.

— By Nancy Wiechec, Catholic News Service