PHILADELPHIA (CNS) — One speaker at the Democratic National Convention didn’t bring the delegates to their feet in cheers, but evoked heads bowed in silent prayer.

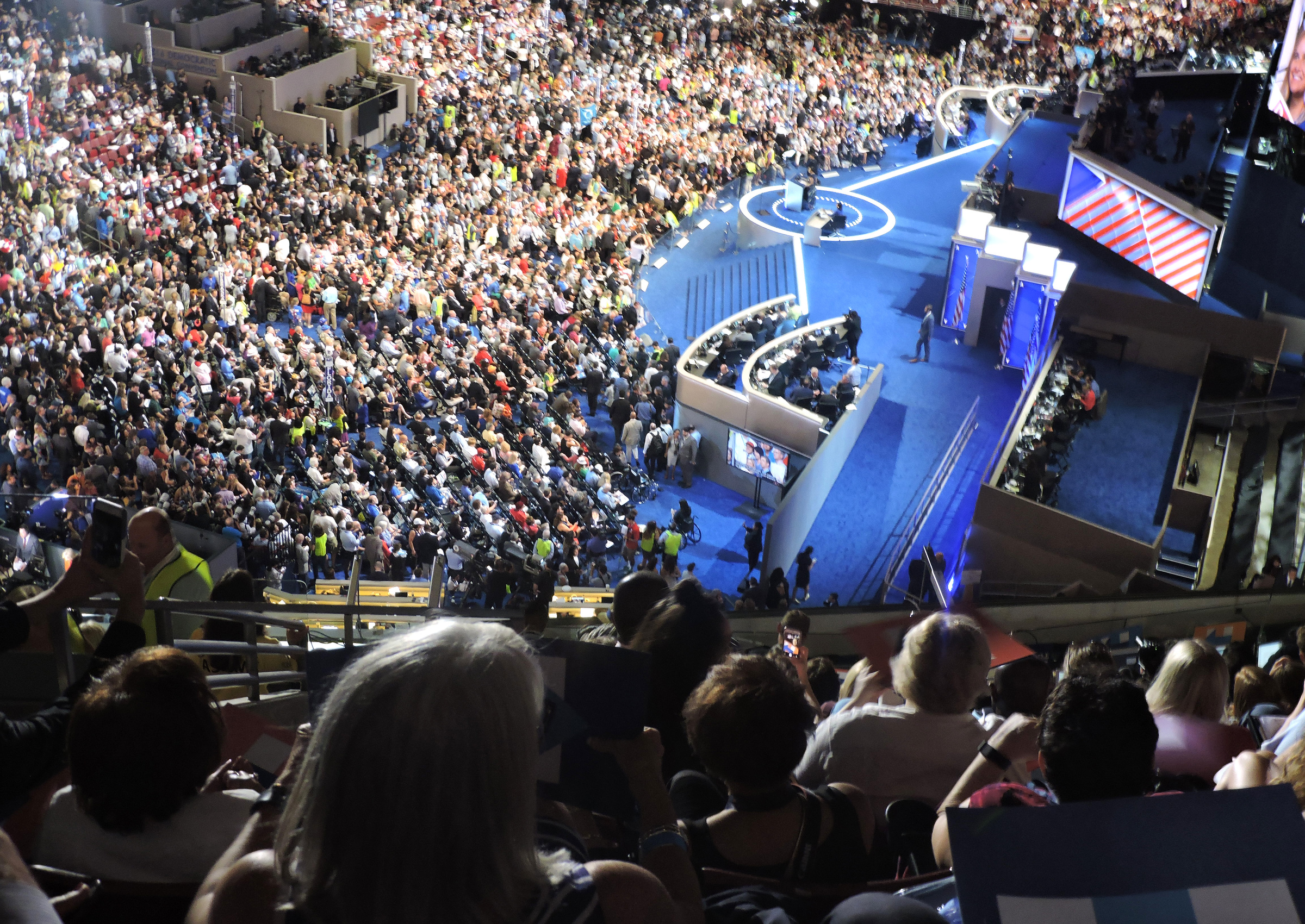

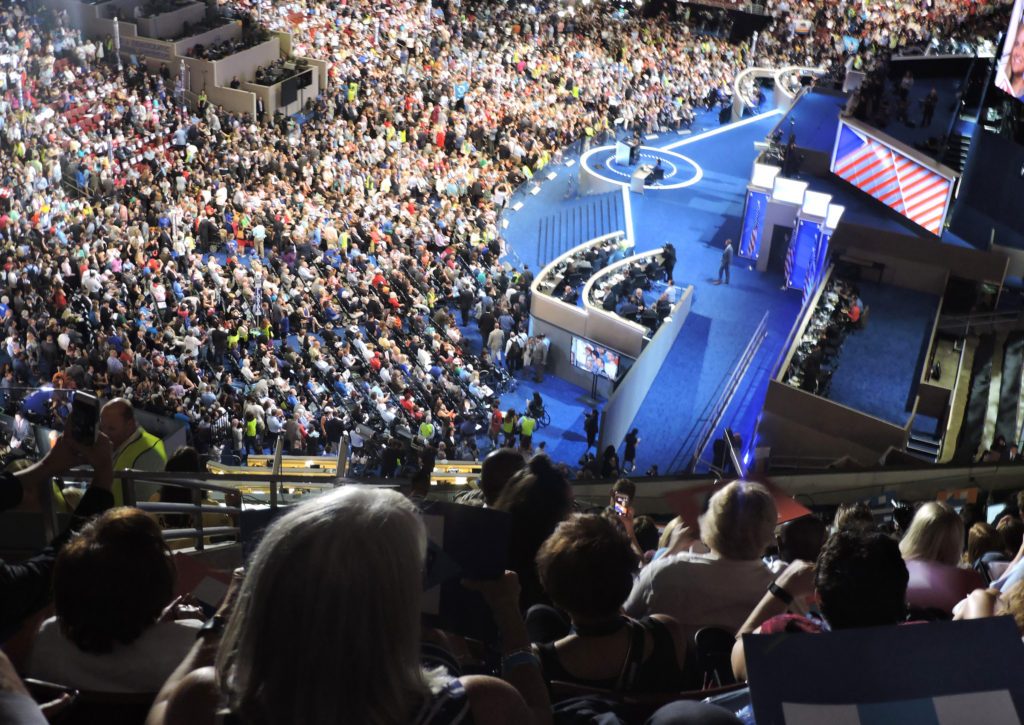

Jesuit Father William Bryon gave an invocation and led more than 20,000 people in prayer July 27 at the Wells Fargo Center in South Philadelphia on the convention’s penultimate night. He preceded two of the party’s biggest names — President Barack Obama and Vice President Joseph Biden — who gave their speeches to roaring acclaim.

In the invocation, Fr. Byron referenced the name of Micah Xavier Johnson, the shooter of five police officers July 7 in Dallas who was later killed by police at an otherwise peaceful demonstration in that city.

The priest said that after the recent violence and “senseless killings” particularly in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Dallas, he was “intrigued” by Johnson’s given name, so he referenced “the prophet Micah and the great St. Francis Xavier in making this invocation.”

Asking everyone to pause silently in prayer, he offered the invocation:

“Lord God, creator and ruler of the universe, we invoke your blessing on this assembly tonight, mindful that you hold our destiny in your hands. Life itself is your gift to us; what we do with our lives is our gift to you.

“Bless us, we pray, as we look to the future of our nation. Keep us free of hatred and violence. Protect us from confusion; we make the words of Francis Xavier our own: ‘In you, O Lord, have I put my hope. Let me never be confounded.’

“And we turn to your prophet Micah to listen to you speak the words that he passed on to us: ‘You have been told, O man, what is good, and what the Lord requires of you: Only to do justice, to love goodness, and to walk humbly with your God’ (Micah 6:8).

“Help us, Lord, to work unceasingly for justice, to know what is good and seek it without fail, and to be truly humble as we walk with you into an unknown but hope-filled future. Amen.”

While Fr. Byron currently is a business professor at St. Joseph’s University in his hometown of Philadelphia, the invitation to speak at the convention came from a connection forged some 15 years ago in Washington.

From 2000 to 2003, he was pastor of Holy Trinity Parish in the capital’s Georgetown section. One parishioner was John Podesta, first a White House staffer and eventually chief of staff in the second administration of President Bill Clinton.

The two struck a friendship that endures today, and it was Podesta who invited his former pastor to speak and who shared time with him Wednesday afternoon and evening.

In his invocation, Fr. Byron linked the themes of looking toward the future, and working for it, with hope. And he believes there is good reason for hope in the future of the United States.

“Hope is a virtue, and we’re a people of hope,” he said, citing 20th-century English writer G.K. Chesterton: “Hope means hoping when things are hopeless, or it is no virtue at all.”

Related

SJU students participate in RNC, DNC seminars

SJU faculty experts on Latino electorate and presidential politics

SJU faculty experts on Evangelical voters and presidential politics

Fr. Byron is hopeful because of “the power of the Holy Spirit” active in this country. Catholics often pray to the Holy Spirit in the words, “Come Holy Spirit, fill the hearts of your faithful and kindle in them the fire of your love. Send forth your Spirit and they shall be created. And you shall renew the face of the earth.”

“We pray that and we believe it,” Fr. Byron told CatholicPhilly.com, the news website of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia.

One feature of America that he hopes to see four years from now, whether in a Clinton or Trump administration, is “a renewal of national community service.” As an example Fr. Byron pointed to the G.I. Bill, which enabled millions of service members returning to civilian life after World War II, including himself, to go to college.

That program produced the largest wave of first-time college students in American history, particularly from 1946 to 1950, contributing to the expansion of post-war prosperity. Fr. Byron sees the G.I. Bill as a watershed moment in American society whose benefits ripple out to the present.

“It is my belief that it was the most creative piece of legislation that ever came out of the political process,” Fr. Byron said. “It was a revolutionary piece of legislation” and a revolution in “big-picture thinking.”

The idea of free college education in return for a period of community service performed by every program participant for up to two years is a concept Fr. Byron has floated consistently in recent years in talks and in his syndicated column with Catholic News Service.

Under a new program like the G.I. Bill, graduates of colleges and universities would be free from the crushing tuition debt experienced by most of today’s students. The societal benefit of a better educated populace with higher incomes and a more robust tax base for society makes the program self-financing, he has argued.