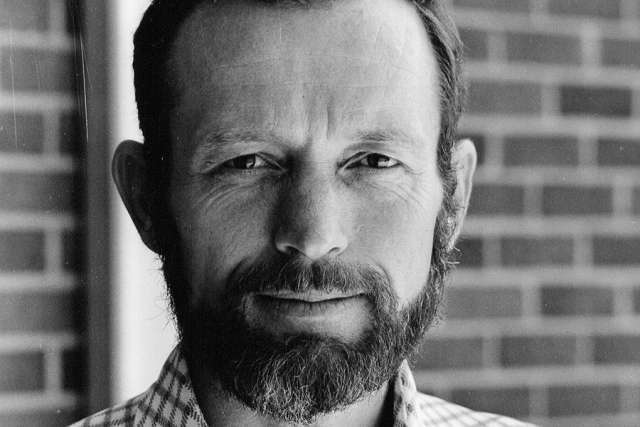

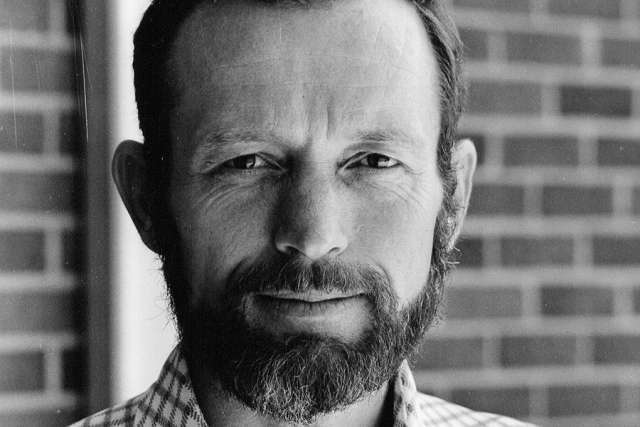

OKLAHOMA CITY (CNA/EWTN News) — Pope Francis has recognized the martyrdom of Father Stanley Rother, a priest of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City who served in Guatemala, making him the first martyr to have been born in the United States.

“Servant of God Fr. Stanley Rother has been approved for beatification!” Archbishop Paul Coakley of Oklahoma City announced on Facebook Dec. 2. “He is the first US born martyr and priest to receive this official recognition from the Vatican! And of course the first from Oklahoma!”

Pope Francis had met with Cardinal Angelo Amato, prefect of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, Dec. 1, approving decrees for several causes of canonization.

Together with that of Fr. Rother, the Pope recognized the martyrdoms of Fr. Vicete Queralt Llloret and 20 companions, killed in the Spanish Civil War, and Archbishop Teofilius Matulionis of Kaišiadorys, a Lithuanian killed by the Soviets in 1962. Also acknowledged were a miracle attributed to the intercession of Venerable Giovanni Schiavo and the heroic virtue of eight Servants of God.

Fr. Rother was born March 27, 1935, on his family’s farm near the unassuming town of Okarche, Oklahoma, where the parish, school and farm were the pillars of community life. He went to the same school his whole life and lived with his family until he left for seminary.

Surrounded by good priests and a vibrant parish life, Stanley felt God calling him to the priesthood from a young age. But despite a strong calling, Stanley would struggle in the seminary, failing several classes and even out of one seminary before graduating from Mount St. Mary’s seminary in Maryland.

Hearing of Stanely’s struggles, Sr. Clarissa Tenbrick, his fifth grade teacher, wrote him to offer encouragement, reminding him that the patron of all priests, St. John Vianney, also struggled in seminary.

“Both of them were simple men who knew they had a call to the priesthood and then had somebody empower them so that they could complete their studies and be priests,” Maria Scaperlanda, author of “The Shepherd Who Didn’t Run,” a biography of the martyr, told CNA.

“And they brought a goodness, simplicity and generous heart with them in (everything) they did.”

When Stanley was still in seminary, St. John XXIII asked the Churches of North America to send assistance and establish missions in Central America. Soon after, the dioceses of Oklahoma City and Tulsa established a mission in Santiago Atitlán, Guatemala, a poor rural community of mostly indigenous people.

A few years after he was ordained, Fr. Stanley accepted an invitation to join the mission team, where he would spend the next 13 years of his life.

When he arrived to the mission, the Tz’utujil Mayan Indians in the village had no native equivalent for Stanley, so they took to calling him Padre Francisco, after his baptismal name of Francis.

The work ethic Fr. Stanley learned on his family’s farm would serve him well in this new place. As a mission priest, he was called on not just to say Mass, but to fix the broken truck or work the fields. He built a farmers’ co-op, a school, a hospital, and the first Catholic radio station, which was used for catechesis to the even more remote villages.

“What I think is tremendous is how God doesn’t waste any details,” Scaperlanda said. “That same love for the land and the small town where everybody helps each other, all those things that he learned in Okarche is exactly what he needed when he arrived in Santiago.”

The beloved Padre Francisco was also known for his kindness, selflessness, joy and attentive presence among his parishioners. Dozens of pictures show giggling children running after Padre Francisco and grabbing his hands, Scaperlanda said.

“It was Father Stanley’s natural disposition to share the labor with them, to break bread with them, and celebrate life with them, that made the community in Guatemala say of Father Stanley, ‘he was our priest,’” she said.

Over the years, the violence of the Guatemalan civil war — which lasted 36 years from 1960-1995 — inched closer to the once-peaceful village. Disappearances, killings and danger soon became a part of daily life, but Fr. Stanley remained steadfast and supportive of his people.

In 1980-1981, the violence escalated to an almost unbearable point. Fr. Stanley was constantly seeing friends and parishioners abducted or killed. In a letter to Oklahoma Catholics during what would be his last Christmas, the priest relayed to the people back home the dangers his mission parish faced daily.

“The reality is that we are in danger. But we don’t know when or what form the government will use to further repress the Church …. Given the situation, I am not ready to leave here just yet… but if it is my destiny that I should give my life here, then so be it …. I don’t want to desert these people, and that is what will be said, even after all these years. There is still a lot of good that can be done under the circumstances.”

He ended the letter with what would become his signature quote:

“The shepherd cannot run at the first sign of danger. Pray for us that we may be a sign of the love of Christ for our people, that our presence among them will fortify them to endure these sufferings in preparation for the coming of the Kingdom.”

In January 1981, in immediate danger and his name on a death list, Fr. Stanley did return to Oklahoma for a few months. But as Easter approached, he wanted to spend Holy Week with his people in Guatemala.

“Father Stanley could not abandon his people,” Scaperlanda said. “He made a point of returning to his Guatemala parish in time to celebrate Holy Week with his parishioners that year — and ultimately was killed for living out his Catholic faith.”

The morning of July 28, 1981, three Ladinos, the non-indigenous men who had been fighting the native people and rural poor of Guatemala since the 1960s, broke into Fr. Rother’s rectory. They wished to disappear him, but he refused. Not wanting to endanger the others at the parish mission, he struggled but did not call for help. Fifteen minutes and two gunshots later, Fr. Stanley was dead and the men fled the mission grounds.

While his body was returned to Oklahoma, his family gave permission for his heart and some of his blood to be enshrined in the church of the people he loved and served. A memorial plaque marks the place.

Fr. Rother was considered a martyr by the Church in Guatemala and his name was included on a list of 78 martyrs for the faith killed during Guatemala’s 36-year-long civil war. The list of names to be considered for canonization was submitted by Guatemala’s bishops to St. John Paul II during a pastoral visit to Guatemala in 1996.

Because Fr. Rother was killed in Guatemala, his cause should have been undertaken there. But the local Church lacked the resources for such an effort. The Guatemalan bishops’ conference agreed to a transfer of jurisdiction to the Oklahoma City archdiocese.

Scaperlanda, who has worked on Fr. Stanley’s cause for canonization, said the priest is a great witness and example: “He fed the hungry, sheltered the homeless, visited the sick, comforted the afflicted, bore wrongs patiently, buried the dead — all of it.”

His life is also a great example of ordinary people being called to do extraordinary things for God, she said.

“(W)hat impacted me the most about Father Stanley’s life was how ordinary it was!” she said.

“I love how simply Oklahoma City’s Archbishop Paul Coakley states it: ‘We need the witness of holy men and women who remind us that we are all called to holiness — and that holy men and women come from ordinary places like Okarche, Oklahoma,’” she said.

“Although the details are different, I believe the call is the same — and the challenge is also the same. Like Father Stanley, each of us is called to say ‘yes’ to God with our whole heart. We are all asked to see the Other standing before us as a child of God, to treat them with respect and a generous heart,” she added.

“We are called to holiness — whether we live in Okarche, Oklahoma, or New York City or Guatemala City.”

Mary Rezac contributed to this report.