WASHINGTON (CNA/EWTN News) — Anti-Catholic state laws from the 19th century are today being used by secularists to fight public funding of all religious organizations, warned a religious freedom advocacy group.

State Blaine Amendment laws are utilized today “to counter religious organizations and religious individuals,” said Eric Baxter, senior attorney at the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty.

“The First Amendment was set in place to ensure that religious beliefs and religious exercise could have an equal part in our public life and culture,” he told CNA.

These state laws, however, “are being used to thwart that, to say that somehow religion is like the ugly stepchild of the family of civil rights, and creates this idea that religion should be sidelined in public life.”

What was the original Blaine Amendment, and how were state laws modeled after it?

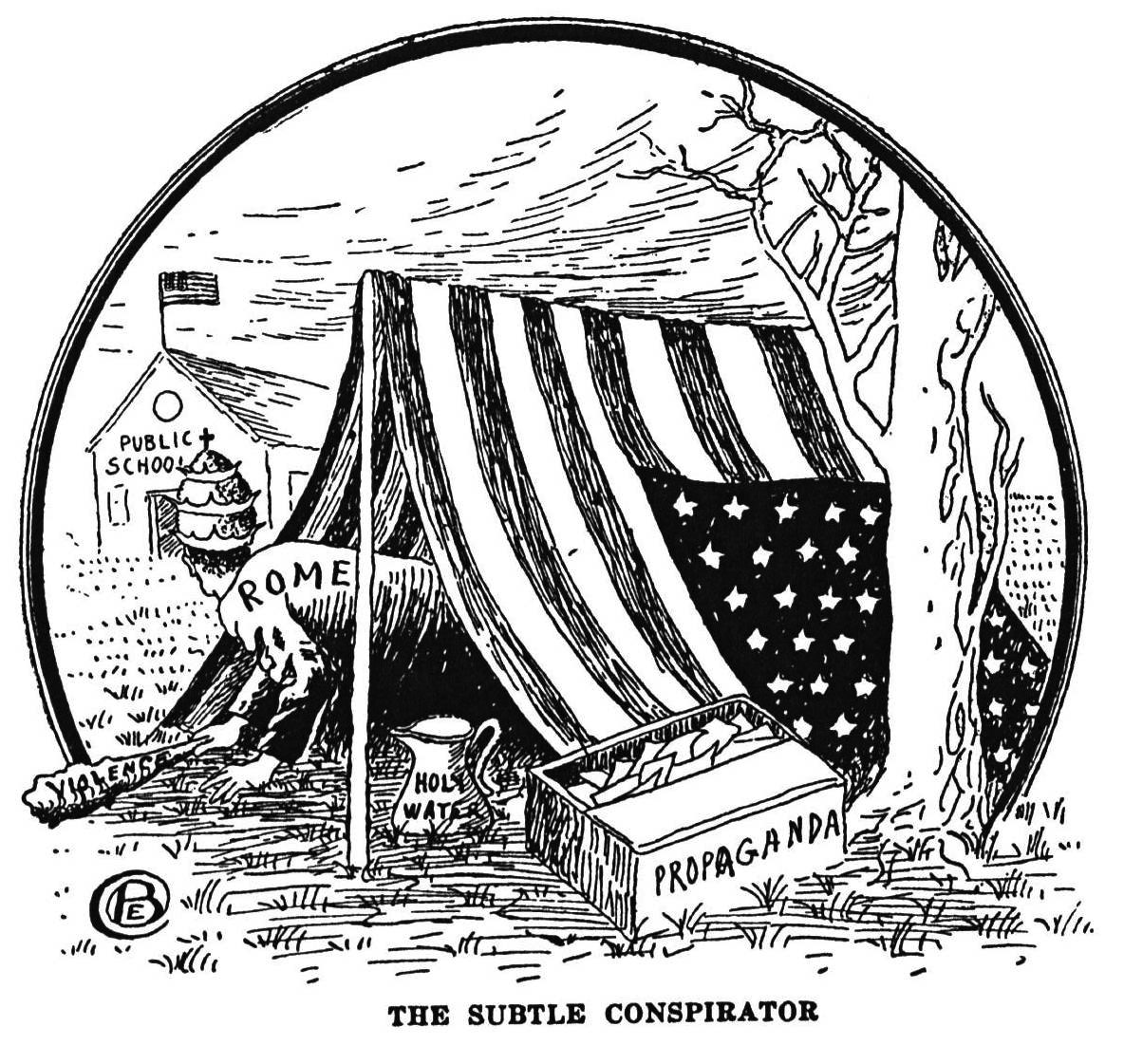

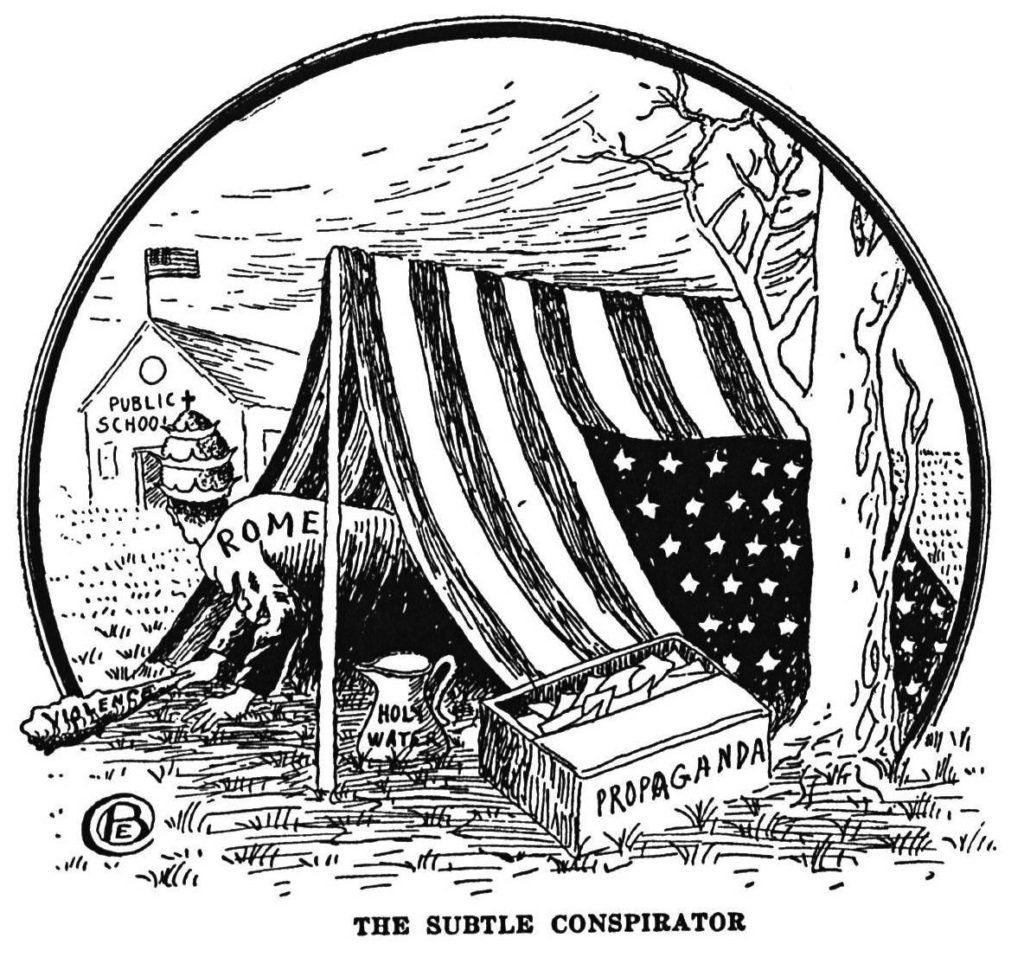

In the years following the Civil War, there was widespread suspicion and even open hostility toward Catholics in the U.S., especially toward immigrant Catholic populations from Europe.

Public schools at the time were largely Protestant, with no single Christian denomination in charge, and many Catholics attended parochial schools which were seen as “sectarian” by prominent public figures, explains historian John T. McGreevy in his book “Catholicism and American Freedom.”

Public figures, he notes, including one current and one future U.S. president at the time, pushed against taxpayer funding of Catholic schools and even advocated for an increase in the taxation of Catholic Church property in the U.S.

Ohio’s Republican gubernatorial candidate and future U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes opposed Catholic priests being able to visit state asylums.

In a speech to Civil War veterans in 1875, President Ulysses S. Grant insisted that no federal money “be appropriated to the support of any sectarian school.”

And, the former general-in-chief of the U.S. armies during the Civil War added, “if we are to have another contest in the near future of our national existence, I predict that the dividing line will not be Mason and Dixon’s but between patriotism and intelligence on the one side, and superstition, ambition, and ignorance on the other.”

As McGreevy noted, “audience members understood” what Grant meant about “superstition,” as he had “referred to a Catholic Church that he saw as increasingly aggressive.”

Grant pushed for a federal amendment by Sen. James Blaine of Maine — himself a future presidential candidate — that prohibited taxpayer funding of “sectarian” schools — the original “Blaine Amendment.” It failed in the Senate, however, although as McGreevy noted some Republican senators, during the debate, cast aspersions toward Catholics as they argued for the passage of the amendment.

Nevertheless, the federal amendment took form at the state level and many states eventually passed versions of the bill barring state funding of Catholic schools.

In the Supreme Court’s 2000 decision Mitchell v. Helms, a four-justice plurality insisted that the Blaine Amendment’s motive to deny public funding of “sectarian” institutions was bigoted.

“Finally, hostility to aid to pervasively sectarian schools has a shameful pedigree that we do not hesitate to disavow,” Justice Clarence Thomas, joined by Justices Anthony Kennedy and Antonin Scalia and Chief Justice William Rehnquist, wrote in the plurality opinion.

“Consideration of the amendment arose at a time of pervasive hostility to the Catholic Church and to Catholics in general, and it was an open secret that ‘sectarian’ was code for ‘Catholic,’” the opinion read. Furthermore, they added, “pervasively sectarian schools” are not blocked by the Constitution from receiving federal funding “from otherwise permissible aid programs.”

“This doctrine, born of bigotry, should be buried now,” they stated.

While they were introduced more than a century ago, these state laws are still in use today against religious organizations, Baxter said. For instance, a case before the Supreme Court involves the Missouri version of the amendment.

Trinity Lutheran Church in Columbia, Missouri, was seeking to enter a state program to receive “used tires from landfills” in order “to create playground material.” The playground is used by the public, but the state denied the church’s participation in the program because it is a religious institution.

It is “blatant discrimination,” Baxter said, given that the state used tire program is a “purely secular program” and “open to everyone, and yet the state saying you can’t participate if you’re religious.”

Other Blaine cases around the country include a church-run program in Florida that met inmates released from prison and connected them with programs to meet their needs of housing, mental health treatment and job training. It had a positive record of preventing recidivism, Baxter said, but atheists sued over the program’s connection with the state.

Although a federal judge ruled in the favor of Prisoners of Christ, “that comes at the cost of years of litigation,” Baxter noted.

In Oklahoma, students with disabilities were not sufficiently helped at the public schools and were instead given scholarships by the government to attend private schools with programs to meet their needsgeor.

A lawsuit was brought against the use of scholarships for religious schools, but the state supreme court ruled in favor of the religious schools despite the state’s Blaine Amendment, Baxter said.

Another state school scholarship program in Georgia was criticized for sending children to Catholic schools on public scholarships, and the state’s Blaine Amendment was used in a lawsuit against the practice.

School cases present a substantial portion of Blaine Amendment cases, Baxter noted, because there are “a number of these programs … where states are trying to figure out how best to provide a publicly-funded education to every student” and incorporate private schools, including religious schools, into the programs.

These state laws are deleterious to religious groups, Baxter insisted, because even if the groups win in court, they are hampered by years of litigation and legal feeds. Also, he added, they “contribute” to “religious strife” in society by marginalizing religious groups.

The laws, when applied against equal participation in state programs by religious groups, are unconstitutional, he argued.

“If they’re applied to discriminate against religious organizations and individuals, and keep them from participating on equal footing with other organizations and state programs, they violate the First Amendment’s free exercise and establishment clauses,” he insisted, “by basically trying to suppress religious believers or penalize religious entities on grounds that aren’t applied to everyone else.”

Their main problem is “this idea that somehow religion is not welcome in public life, when really, the First Amendment was created to ensure just the opposite,” he said, “to remind us that religion is a part of what it means to be a human being.”