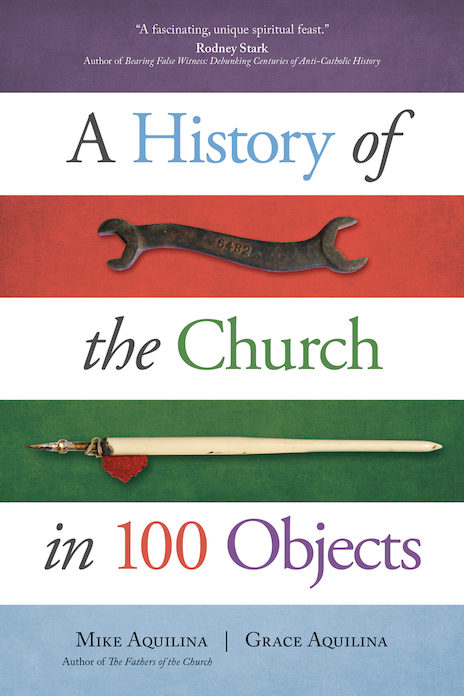

What could Christopher Columbus’ compass, the Wittenberg door and the curls of St. Therese of Lisieux possibly have in common? All, it turns out, reveal memorable stories about the history of the church.

Publisher: Ave Maria Press, Notre Dame, Indiania, 2017

Length: 410 pages

Order now $24.95

Mike and Grace Aquilina have found an accessible and fascinating way to tell this story: through the history, in words and full-color photos, of 100 well-chosen objects and places.

Viewing the image of Columbus’ compass in its weathered wooden box…

…helps bring home the perils of his four trans-Atlantic voyages in the time of Ferdinand and Isabella. We can easily see him gripping this diminutive tool in a storm that is said to have “almost killed him” — an experience that he apparently interpreted as God’s rightful punishment for his sins. In his diary, Columbus demonstrates a certain piety, as he names geographical features for saints, the Trinity and other mysteries of faith. He even predicts that the New World’s native peoples will “eagerly embrace Christianity.”

A generation later in 1517, Martin Luther nailed his “Ninety-Five Theses” to the door of All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg, Germany…

…leading to the Reformation that rocked Europe. In Germany this schism led to a bloody religious war that wasn’t settled until 1555. The accompanying photo for this entry depicts the tall bronze door inscribed with Luther’s complete text (a replacement for the original wooden doors that a fire destroyed in the 18th century). Luther himself, we are told, is buried inside.

An arresting photo shows St. Therese’s (1873-1897) long blond curls…

shorn when she became a Carmelite nun, arranged artfully and framed in a shadowbox that hangs above her bed in her childhood home in Lisieux. This image makes the Little Flower tangibly real to us, as the authors describe her “Little Way” philosophy of small daily sacrifices such as befriending “sisters who were socially awkward and whom she found, actually, to be off-putting.” Another example is Therese’s practice of writing letters to cheer faraway missionaries. She always tried to perform such small but meaningful actions with “extraordinary love,” and her example inspired many later spiritual leaders such as Dorothy Day.

Mike Aquilina has written dozens of books, including “The Fathers of the Church,” and this is his first collaboration with his daughter Grace Aquilina, a writer.

Their book is divided into seven historical sections:

- the church of the apostles and martyrs (e.g., the chains of St. Peter in Rome, Diocletian’s tomb)

- the church and the empire (St. Ambrose’s bones, a Milan baptistery)

- the Dark Ages (St. Boniface’s ax, a scribe’s stylus)

- the Middle Ages (the Holy Grail, the rose window at Notre Dame)

- Renaissance and reformations (rosary beads, Michelangelo’s “Pieta”)

- the age of revolutions (the guillotine, holy water bottles)

- the global village (Pope Benedict XV’s fountain pen, a concentration camp sign)

Each entry aims to tell the church’s story through material culture, from humble everyday items like newspapers and paving stones to priceless works of art.

As the authors write in their introduction, “Salvation history … doesn’t occur in moments shrouded in mists before time. It doesn’t take place on the heights of Mount Olympus, invisible to us mere mortals who live at sea level.” Rather, it “is the story of God entering our world, sometimes with flash and dazzle, but most often through ordinary stuff amid the mess of centuries.”

Accordingly, recording these stories in books is only a first step; we also “preserve the memory in memorials, monuments and museums.”

An intriguing surprise is the inclusion of St. Hildegard of Bingen in an entry about, of all things, a medieval beaker — rather than in a section dealing with her mystical visions or her music.

The authors do this to underscore that this medieval abbess of a monastery of nuns was a “pioneering thinker” who actually wrote medical and scientific works that sparked a renewal of interest in the natural sciences. One, her “Physica,” was a compendium of healing herbs, minerals, and even the organs of animals. Another, “Causes and Cures,” aided diagnosis through its detailed observations about various illnesses and their remedies.

Discussion of St. Hildegard’s contributions to science is paired with those of St. Albert the Great, like her a German saint with wide-ranging academic interests.

Another unexpected entry discusses the Pill. What exactly can the story of this oral contraceptive reveal about the church’s history? Plenty, it turns out, because by dissociating sex from procreation, this drug changed society and culture profoundly.

The authors trace this history and conclude with a negative assessment of the pill’s impact, including its objectification of women as “mere instruments of pleasure” (something which Pope Paul VI had predicted in his 1968 encyclical, “Humanae Vitae”).

Interestingly, as a young bishop, Karol Wojtyla (later Pope John Paul II) was a member of Pope John XXIII’s special commission to study the morality of artificial birth control in the early 1960s. It’s likely that this experience informed his later addresses on the subject (collectively entitled the “theology of the body”) that affirmed church teaching in a holistic way.

Richly detailed, “A History of the Church in 100 Objects” is an engaging look at a collection of objects that ranges across the world and across time. Together, they reveal the universality of the church through the ages and also its continuity.

Roberts directs the journalism program at the State University of New York at Albany and has written two books about Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker.