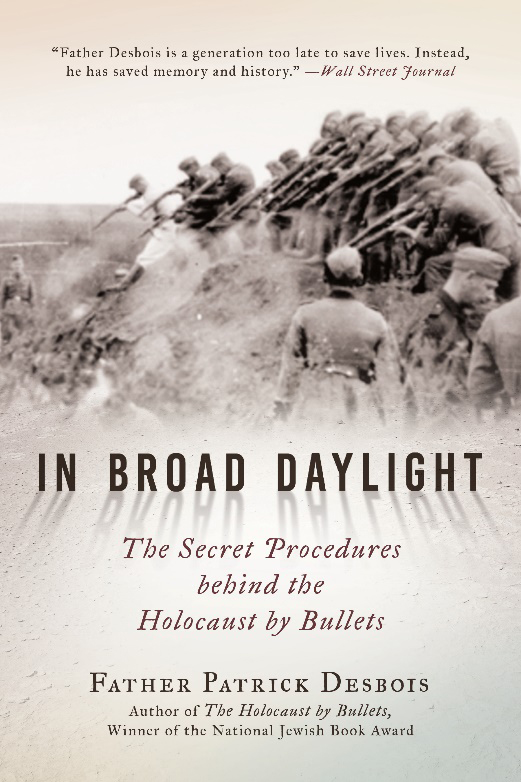

‘In Broad Daylight: The Secret Procedures Behind the Holocaust by Bullets’

Author: Fr. Patrick Desbois

Publisher: Arcade Publishing

Length: 281 pages

Cost: $24.99

Release Date: Jan. 23, 2018

By Agostino Bono

Catholic News Service

This book is chilling reading. One wishes it were a novel rather than a factual recounting of the Nazi World War II slaughter of Jews in what was then the Soviet Union.

“In Broad Daylight” documents how the Nazi Holocaust was not limited to Central and Western European concentration camps. More than 2 million Jews were also killed in the German-occupied Soviet Union. Unlike the concentration camp massacres that were conducted behind closed doors, the slaughters in Soviet territories were executions by firing squads performed in broad daylight in rural villages with local townspeople recruited as willing or forced participants.

Based on 4,000 eyewitness interviews supplemented by depositions given in war crimes trials found in German and Russian archives, this book provides first-person accounts of the horrors.

The author, Fr. Patrick Desbois, is a French Catholic priest, born 10 years after the war’s end. In 2004 he founded Yahad-In Unum (Togetherness in One) dedicated to documenting these massacres and finding and commemorating the unmarked mass graves. He has advised the French bishops on Jewish-Catholic relations and is a professor of Holocaust history at Georgetown University in Washington.

His book offers grisly slices of life cut from the racist fruit of anti-Semitic genocide. Published at a time when Holocaust denials dot the European landscape and white supremacy gains traction in the United States, it is a sharp warning of the dangers lurking when peoples or nations begin sliding down the slippery slope of racist ideologies.

The interviews collected by Fr. Desbois and his researchers narrate how the German military sent mobile units into occupied rural towns to methodically organize mass executions with mechanical precision. The killing crews even recruited cooks in the morning so that a hot meal would be ready for them when they took their lunch break.

Those interviewed were children when the events, etched into their minds, happened. As the killings were done in broad daylight, they were eyewitnesses and often participants, seeing their neighbors, schoolmates and shopkeepers executed. They tell how local villagers were recruited as policemen and gravediggers, and aided in the transporting of Jews to the killing sites.

The night before would often see soldiers raiding Jewish homes to rape the women. The next day, at the execution site Jews were stripped to their underwear so the clothes could be searched for valuables sewed inside the linings. Among those executed were women clutching months-old babies and crippled old people carried to the site by relatives.

In a war crimes deposition, one German soldier who was not a member of the killing crew recounts how he was encouraged by his commander to witness the executions. While watching, he recalls, a Jewish woman broke away, running toward him pleading to be saved. His account adds that, an executioner pursued her and shot her in the back of the head.

The aftermath of the executions included raiding Jewish homes to take away valuables and clothes that would be auctioned off or given to collaborators as rewards.

Some stories told of resistance. One person narrates how he came across two Jewish women who had escaped the roundup and he was able to hide them in a relative’s home. Not all these efforts were successful. Germans did spot raids on non-Jewish homes to see if these were Jewish hideouts.

The book confronts readers with a harsh historical reality, one that shows the need to constantly be vigilant against hate-filled ideologies before they become cornerstones of public policy.

Agostino Bono is a retired CNS staff writer.