By Joyce Duriga

Catholic News Service

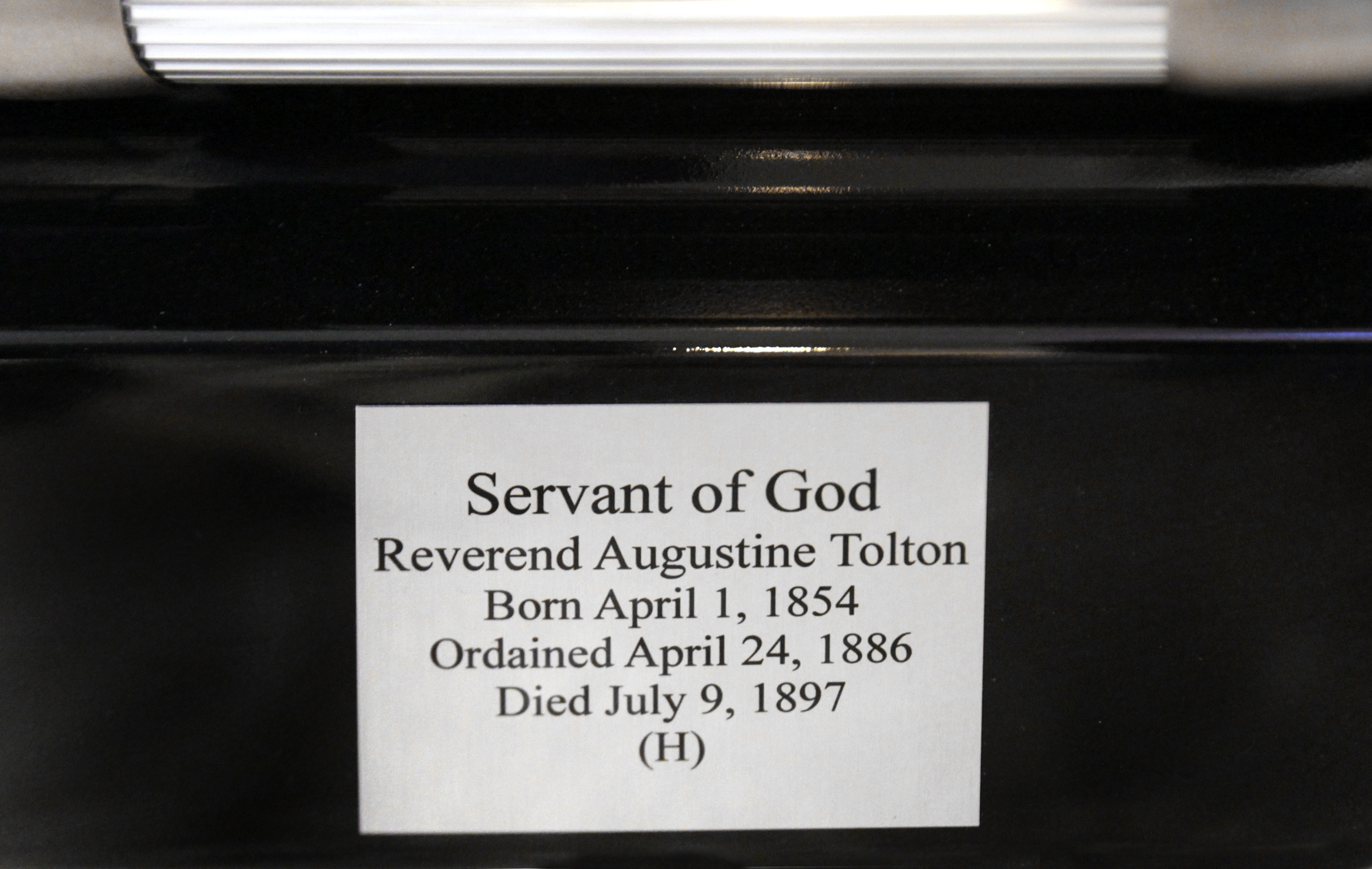

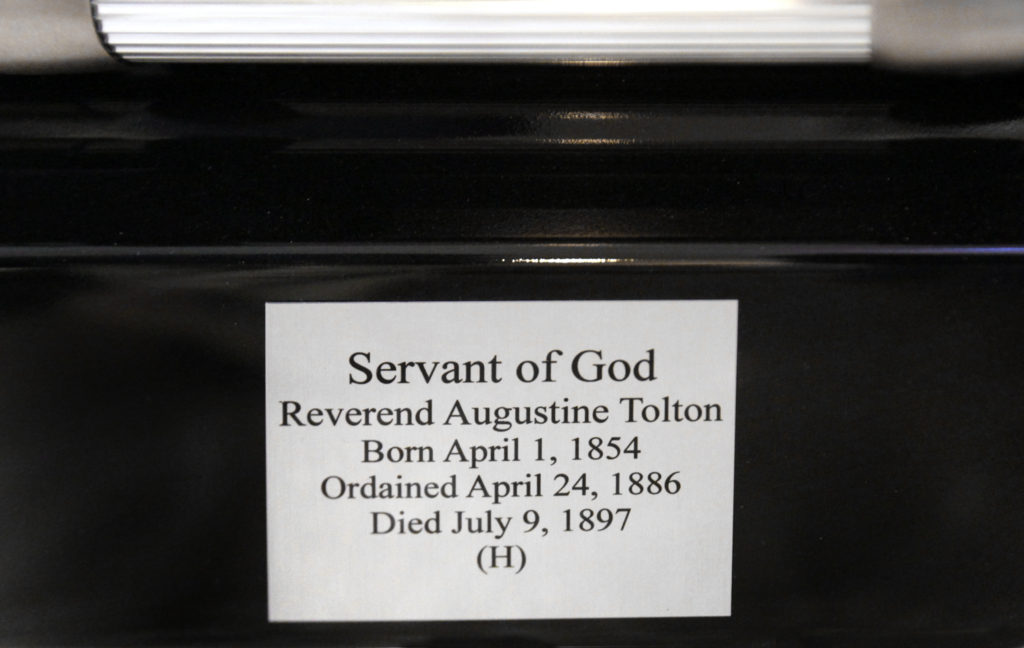

Servant of God

Fr. Augustus Tolton

Born: April 1, 1854

Ordained: April 24, 1886 at St. John Lateran Basilica for the Diocese of Alton (now Springfield)

Assigned to the Archdiocese of Chicago: Dec. 19, 1889

Died: July 9, 1897

Declared Servant of God: Feb. 13, 2012

CHICAGO (CNS) — The canonization cause of Fr. Augustus Tolton received important approval from the Vatican’s historical consultants earlier this year, moving the cause forward.

Fr. Tolton, a former slave, is the first recognized U.S. diocesan priest of African descent. Chicago Cardinal Francis E. George opened his cause for canonization in 2011, giving the priest the title “Servant of God.”

The consultants in Rome ruled in March that the “positio” — a document equivalent to a doctoral dissertation on a person’s life — was acceptable and the research on Fr. Tolton’s life was finished, said Chicago Auxiliary Bishop Joseph N. Perry, postulator for the cause.

“They have a story on a life that they deem is credible, properly documented. It bodes well for the remaining steps of scrutiny — those remaining steps being the theological commission that will make a final determination on his virtues,” Bishop Perry explained.

It now goes to the Congregation for Saints’ Causes, he said. Once the congregation’s members “approve it, then the prefect of that congregation takes the case to the pope,” he added.

If the pope approves it, Fr. Tolton would be declared Venerable, the next step on the way to canonization. The last two steps are beatification and canonization. In general, two approved miracles through Fr. Tolton’s intercession are needed for him to be beatified and canonized.

Six historical consultants ruled unanimously on the Tolton “positio,” compiled by a team in Rome led by Andrea Ambrosi, based on hundreds of pages of research completed in Chicago.

While working on the document, Ambrosi’s team asked Bishop Perry why it took so long to open a cause for Fr. Tolton, who died in 1897.

“We told them that African-Americans basically had no status in the Church to be considered at that time. Some people didn’t think we had souls. They were hardly poised to recommend someone to be a saint,” Bishop Perry said. “And then in those days there were hardly any saints from the United States proposed.”

The fact that the historical consultants approved the “positio” unanimously is a positive sign, he said. The cause is scheduled to go before the theological commission in February 2019.

Two miracles through Fr. Tolton’s intercession have been sent to Rome.

“We’re hoping and our fingers are crossed and we’re praying that at least one of them might be acceptable for his beatification,” Bishop Perry said.

Born into slavery, young Augustus fled to freedom with his mother and two siblings through the woods of northern Missouri and across the Mississippi River while being pursued by bounty hunters and soldiers. He was only 9 years old.

The small family made their home in Quincy, Illinois, a sanctuary for runaway slaves.

Growing up in Quincy and serving at Mass, Augustus felt a call to the priesthood, but because of rampant racism, no seminary in the United States would accept him.

He headed to Rome, convinced he would become a missionary priest serving in Africa. However, after ordination he was sent back to his hometown to be a missionary to the community there.

He was such a good preacher that many white people filled the pews for his Masses, along with black people. This upset the white priests in the town, who made life very difficult for him as a result. After three years, Fr. Tolton moved north to Chicago to minister to the black community, at the request of Archbishop Patrick Feehan.

Fr. Tolton worked tirelessly for his congregation in Chicago, to the point of exhaustion. On July 9, 1897, he died of heat stroke while returning from a priests retreat. He was 43.

Since the cause was opened, Bishop Perry and his team have given more than 170 presentations on Fr. Tolton around the country. They also have received inquiries about the priest from Catholics in the Philippines, Germany, Australia, Italy, France and countries in Africa.

People receive Fr. Tolton’s story well, Bishop Perry said.

“There’s also the element of surprise. … People always presume that we had black priests,” he told the Chicago Catholic, the archdiocesan newspaper.

“There’s an element of surprise at how the Church handled some of these more naughty issues of reception and acceptance,” said the prelate, who is African-American. “They thought that this was pretty usual, but they were surprised to see that there were certain individuals who were not so receptive to a person like (Father) Tolton and others.”

Fr. Tolton did not speak out publicly against the racist abuse he encountered from his fellow Catholics. Rather, throughout his ministry, he preached that the Catholic Church was the only true liberator of blacks in America.

“I think people generally are touched by his story, especially regarding his stamina and perseverance given what appears to be a different mood today. People don’t accept stuff thrown in their faces anymore,” Bishop Perry said.

Joyce Duriga is editor of the Chicago Catholic, newspaper of the Archdiocese of Chicago.