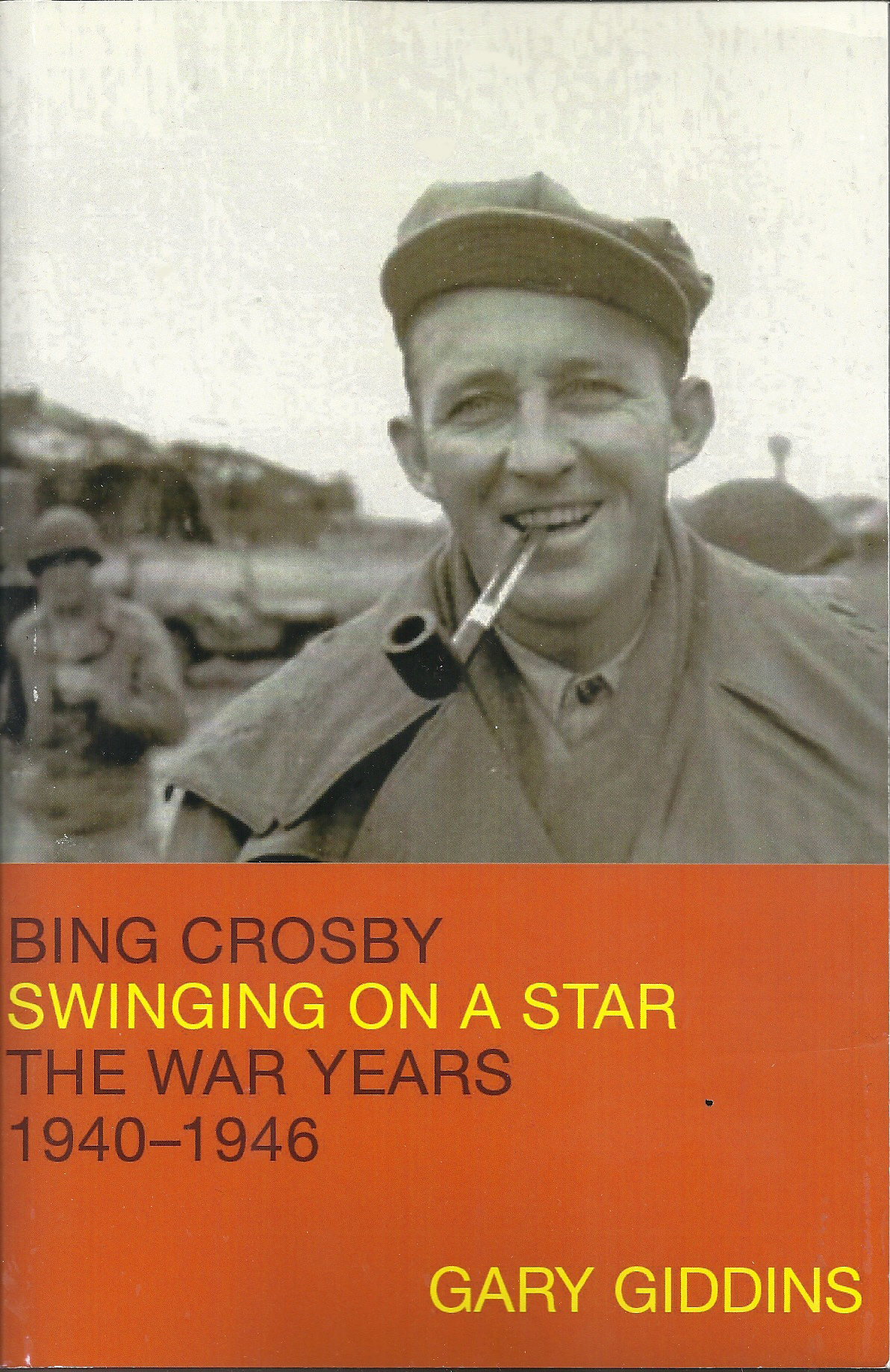

‘Bing Crosby, Swinging on a Star, Vol. 2: The War Years, 1940-1946’

Author: Gary Giddins

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Length: 736 pages

Release Date: Oct. 30, 2018

By Kurt Jensen

Catholic News Service

NEW YORK (CNS) — Affable fictional clergyman Fr. Charles “Chuck” O’Malley was the principal figure in two well-received World War II-era movies, 1944’s “Going My Way” and its 1945 sequel, “The Bells of St. Mary’s.”

These gentle portrayals of faith in action not only resonated with Catholic viewers across generations but also changed the life of the famous actor who portrayed O’Malley.

So, concludes Gary Giddins in “Bing Crosby: Swinging on a Star” (Little, Brown), the second volume of his biography of the versatile entertainer, which will be published Oct. 30. The first volume, subtitled “A Pocketful of Dreams,” appeared in 2001.

The new tome covers the years 1940 through 1946, the prime of the crooner’s career. This was the peak of Crosby’s cultural influence, exerted on radio, vinyl and the screen. Songs such as the totemic “White Christmas” gained huge popularity — as did his partnership with Bob Hope and Dorothy Lamour in the freewheeling “Road” comedies.

Giddins, a veteran jazz critic and music biographer, is more assured when he’s limning Crosby’s singing style and recordings than when he’s discussing films or Catholicism or Crosby’s often-stormy family life.

Fr. O’Malley, though, gets the deference awarded a national monument. Four of the book’s 24 chapters are devoted to the character and his creators, including director Leo McCarey. That’s considerably more attention than Hope receives in the other 20.

“I’m not saying how ‘The Bells of St. Mary’s’ affected Crosby — but he invites his friends over for open house Sunday, and then passes the plate!” Hope quipped at the 1946 Academy Awards.

Giddins doesn’t joke, though. He writes that, for “Going My Way,” McCarey and Crosby “concocted a fantasy priest — a perfect, albeit celibate, man. The costume, a white collar and straw boater, and the trappings, a crucifix and golf clubs, underscore the curious gloss of religious vocation and musical avocation. Liberated from romance, venality and vainglory but not from intrigue and statecraft, Fr. O’Malley emerged as a superhuman fount of liberal wisdom, empathy and action.

“As emblematic of the war years as Atticus Finch was to the civil rights era (and inspiring seminarians much as Atticus did law students), O’Malley represented a righteousness people could feel and believe in. … It proved to (Crosby), though he never quite admitted it — modesty forbade — that he really and truly could act.”

Giddins doesn’t back up that stirring passage thoroughly, particularly the mention of inspired seminarians. But he does provide evidence that O’Malley could be held up to restrain the singer.

One example: Early in 1946, Crosby, in New York, visited the city’s archbishop, Cardinal Francis J. Spellman, the powerful “antipode of Father O’Malley,” as Giddins calls him. Crosby wanted to discuss a possible split from his wife, Dixie, whose alcoholism had grown worse. At the time, he was considering marrying the actress Joan Caulfield.

“The visit to Spellman,” Giddins writes, “was seen by her family as evidence of his intentions. If he expected an ecclesiastical solution, he was disappointed. In the account he gave of the meeting, as remembered by (Joan’s sister) Betty Caulfield, ‘Cardinal Spellman said, “Bing, you are Father O’Malley and under no circumstances can Father O’Malley get a divorce.’” Betty added, ‘I think that was the beginning of the end for Joan and Bing.’”

The influence of movies was taken so seriously in that era that Spellman even wrote to McCarey to stress “the great calamity to the Church and family life everywhere” should Crosby’s divorce occur. It never did. Dixie died of ovarian cancer in 1952. Crosby remarried in 1957 and died in 1977.

If Crosby had any apprehension about portraying a priest, after several years of playing carefree romantic leads, Giddins hasn’t uncovered it. Instead, he writes that Crosby “desperately wanted to make” “Going My Way” based on his trust in McCarey, but that Paramount executives were worried that the film would fail.

The hit song from the first movie, “Swinging on a Star,” originated when McCarey suggested to songwriters Johnny Burke and Jimmy Van Heusen his “idea of music that taught biblical lessons.”

The Production Code Administration fretted over any scenes that showed lingering romantic tension between Fr. O’Malley and his old flame, Genevieve Linden (played by opera singer Rise Stevens). “But the whole point of O’Malley,” Giddins writes, “is that, like Augustine, he has experienced life, made a choice, a sacrifice, found freedom in conversion and does not look back.”

There were fewer concerns about any lovelorn gazes between Fr. O’Malley and Ingrid Bergman’s Sr. Mary Benedict (named after McCarey’s aunt, an Ursuline nun) in “The Bells of St. Mary’s.” But RKO studio chief Charles Koerner feared that the improvised children’s Christmas pageant would offend Catholics and got newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst to agree with him. McCarey rallied clergy support, and the pageant stayed in.

Crosby requested one change for Fr. O’Malley that only sharp-eyed viewers can detect. He’d worn toupées throughout his film career when he couldn’t wear a hat in a scene. And this time, “he requested a modification, a wig to distinguish O’Malley from the familiar Crosby characters.”

Famed Hollywood salon the House of Westmore “came up with a credible wig, wavy, combed to the side, reducing the usual pompadour flip. It did the job but served so clearly as gilding for this particular character that Bing could never use it again.”

The most famous line in “The Bells of St. Mary’s” was Bing’s suggestion: “Just dial ‘0’ for O’Malley,” which is used twice, was not in the screenplay. When it ended the scene in which Sr. Mary Benedict departs for a sanitarium, where she’ll be treated for tuberculosis, and there was “not a dry eye in the house,” Giddins writes.

“Here we have the parting … of a man and woman in the spring of their lives, sharing a chaste love and understanding that will bind them always.”

Kurt Jensen is a guest reviewer for Catholic News Service.