The Church in El Salvador is observing a jubilee year to mark the 40th anniversary of the March 24, 1980, assassination of St. Óscar Romero, while other churches in the United States, Britain and throughout Latin America are holding their own commemorations.

In the Bible, 40 years is a generational measurement of time: For example, God casts the Israelites into the desert for that long, “until the whole generation that had done evil in the sight of the Lord had disappeared” (Nm 32:13). St. Romero’s 40 years appear to take on similar proportions.

When St. Romero’s canonization cause seemed at a standstill, Salvadoran Cardinal Gregorio Rosa Chávez would say he was not going to be beatified until the generation of his contemporaries had passed away, so that his legacy could be assessed dispassionately, without the fanaticism of his detractors or most ardent followers.

After 40 years, so much has changed that it seems an epochal shift has taken place. The change is particularly stunning in El Salvador.

St. Romero’s biggest detractors there are gone. The Salvadoran death squad leader, Roberto D’Aubuisson, reputed to have ordered the killing, died of cancer in 1992.

The Salvadoran political landscape has been made over dramatically.

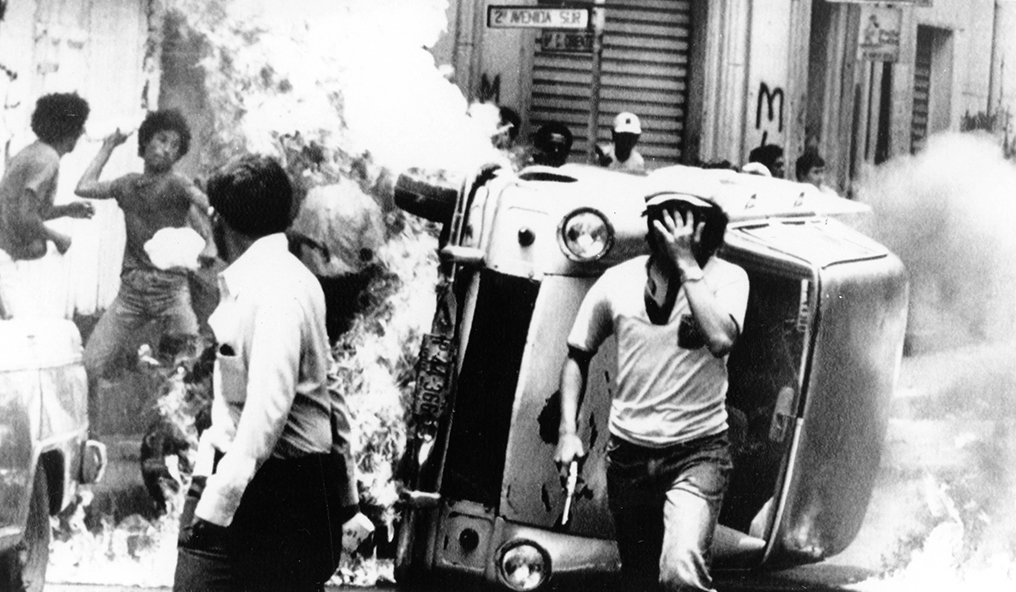

For the first 10 years following the archbishop’s death, the Salvadoran government did not allow public commemorations of him. Later governments, run by D’Aubuisson’s party, tried to relegate then-Archbishop Romero to oblivion. Officialdom refused to celebrate him, while Salvadoran presidents visited D’Aubuisson’s grave every year.

After decades of hostile treatment, in 2005, Salvadoran President Tony Saca, who had been an altar server for Archbishop Romero, called on Pope Benedict XVI to hasten the Salvadoran’s canonization. His successor, President Mauricio Funes, made the archbishop a standard-bearer for the first leftist postwar government.

St. Romero’s death occurred in a Cold War context, but one of the adversaries in that historic rivalry — the Soviet Union — has disappeared from the scene. Even U.S. leaders have come around, a process that culminated with U.S. President Barack Obama visiting St. Romero’s tomb in 2011, a move that would have seemed unthinkable when the archbishop was killed.

At the 40th anniversary of the saint’s martyrdom, El Salvador itself is barely recognizable. A new party, formed in the postwar climate and led by a millennial president, is now in office.

There also was a generational shift toward St. Romero within the Catholic Church, which cleared his path to sainthood. Colombian Cardinal Alfonso López Trujillo, an ardent opponent of the archbishop’s canonization, died in 2008. Another staunch opponent, Cardinal Darío Castrillón Hoyos — also Colombian — died in 2018, just months before the archbishop’s canonization.

Even though Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI initiated and advanced St. Romero’s canonization, the election of a Latin American pope signaled a paradigm shift in the process. Pope Francis, who saw the sainthood cause across the finish line, was keenly familiar with St. Romero and seemed very sympathetic to his cause.

The Salvadoran bishops’ conference has also been reshaped. During St. Romero’s time, all but one of his fellow bishops opposed him. When St. John Paul first visited in 1983, one bishop infamously told the pope that Archbishop Romero was responsible for the civil war dead because he had fanned the flames of class conflict. By the time of his beatification, a long parade of bishops from the region donned vestments reflecting the archbishop’s episcopal seal and replicas of his miter for the occasion.

St. Romero has not, however, pulled off a clean sweep. Even though four martyrs from his time and in his mold are due to be beatified, there are limits to the makeover surrounding the saint’s legacy.

In the days following his canonization, there were some calls for St. Romero to be declared a “doctor of the Church,” a title accorded to certain saints based on the impact of their teaching. Current San Salvador Archbishop José Luis Escobar Alas pitched the idea at an audience with Pope Francis the day after the saint’s canonization. The Vatican has discreetly responded that the time is not yet ripe for such a recognition, which requires a finding that a saint’s influence is broadly accepted throughout the Church.

Forty years after his assassination, Archbishop Romero has clearly gone from persona non grata to a vaunted model of holiness for the faithful. That would seem to constitute a generational shift of biblical proportions. St. Romero has not, however, seeped so deeply into the Church’s bloodstream that his teachings are known and accepted by everyone. That miracle is pending.

— By Carlos Colorado, Catholic News Service. Colorado is an attorney in Los Angeles who has written extensively about St. Óscar Romero and his legacy.