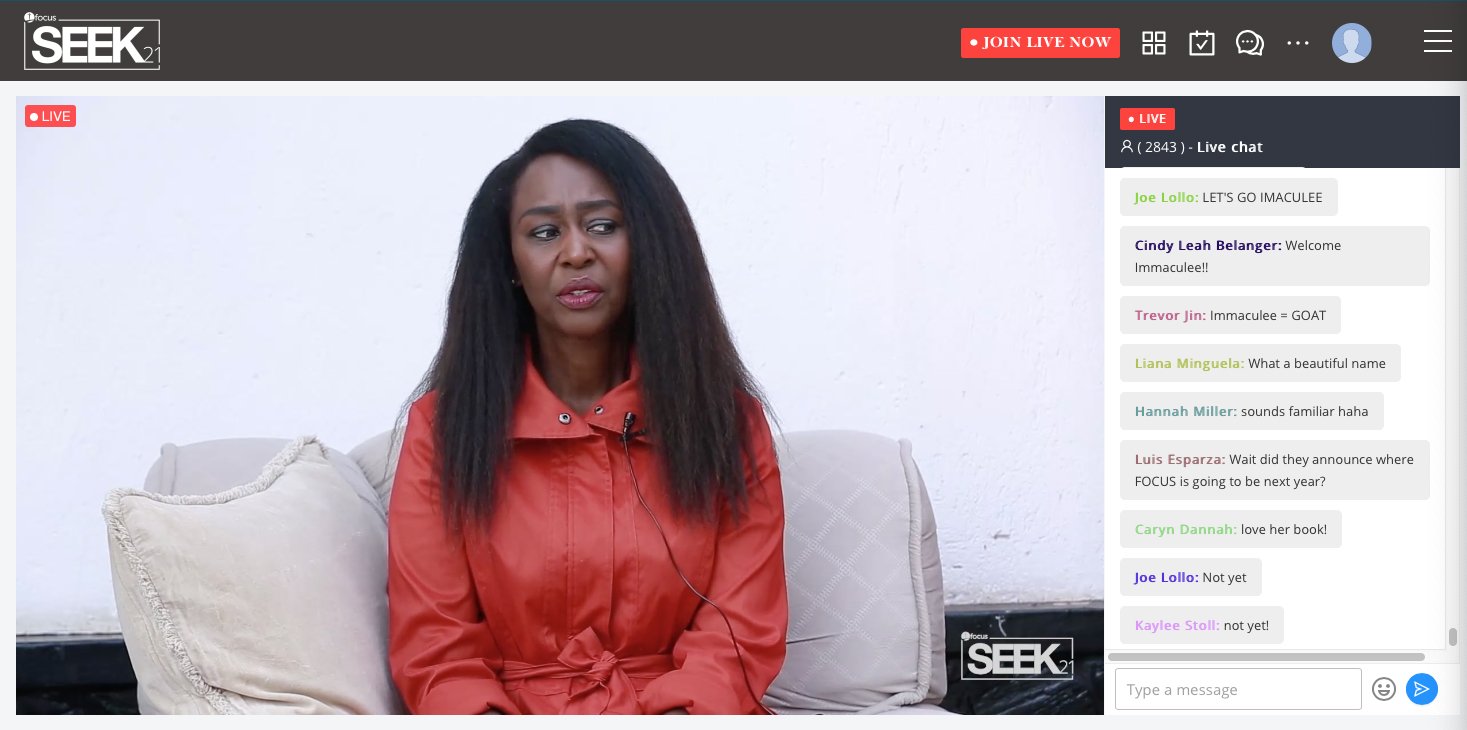

ORLANDO, Fla. (CNS) — Immaculee Ilibagiza found freedom in forgiveness after seeing her family wiped out by genocide in Rwanda, and she shared her extraordinary journey toward that forgiveness in an evening keynote Feb. 5 during the SEEK21 conference.

She was one of two keynote speakers who addressed the theme of forgiveness; the other was Edward Sri, a theologian, author and a founding leader of the Fellowship of Catholic University Students, which sponsored the annual Feb. 4-7 conference, which was held online this year and drew over 26,000 participants from across the globe.

Holding her father’s rosary in her left hand, Ilibagiza shared her story of suffering and how she discovered forgiveness of her sins could set her free and forgiving the crimes of others also could lift pain from her heart.

Today, Ilibagiza is an international speaker who previously worked for the United Nations. But in 1994, she was a student who lived in a small village in Rwanda.

On April 6, 1994, dictator and president of Rwanda Juvenal Habyarimana was assassinated, which put militant Hutus in charge of the government. In the 100 days that followed, 800,000 to over a million Rwandans — Tutsis and some moderate Hutus — were slaughtered by their countrymen and, in some cases, their next-door-neighbors.

“We knew it was coming. Hatred had spread among the two tribes on the radio. That radio was hired by the government to spread hatred among people,” said Ilibagiza, a member of the Tutsi tribe who was raised Catholic. Most members of her family were brutally murdered.

The entire village feared the days ahead and many arrived at Ilibagiza’s home, where her parents were highly respected and loved. The government had already forced a shutdown and borders had been closed. People were being killed family by family, including 18 families in a two-hour period of time.

“By the second day, we had 10,000 people around our house,” Ilibagiza explained and while the people might have gathered for words of hope, her father spoke realistically about impending death. “He said they should use the time to ask for forgiveness. He said, ‘Let’s repent and ask forgiveness so we can go to heaven.’ People were listening and praying.”

Before bloodshed arrived at her village, Ilibagiza’s father gave her his rosary and told her to seek shelter at a neighbor’s house. He was a Hutu and was willing to shelter her and seven other women. They were kept in a bathroom that was 3 feet by 4 feet. The women literally sat on one another and were told not to make a noise. They stayed there for 91 days.

Silence and starved, by the end of the first week Ilibagiza asked the Hutu man if he could put on the radio briefly so they could hear what was happening in her country.

“I couldn’t believe it. The leaders in the country was asking to kill anyone of my tribe,” she said, adding she recognized one of the voices of the officials calling for the genocide.

“He was a man who earned a Ph.D. in France. And he was saying, ‘Don’t forget the children. A snake is a snake. We must cleanse the country,'” she said. “That was a big lesson for me. … It was a moment that I realized you can educate your mind, but if you don’t have love in heart, it is meaningless. It is the first time I truly understood that faith means so much more than what we learn in school.”

In those 91 days of silence, Ilibagiza examined her own faith and relationship with God. She described her fear and anxiety as “a thousand needles through her body” and a voice in her head told her to open the door of the bathroom and end the suffering.

But another voice told her, “Remember, ask God to help you. God is almighty. He can do anything.” She mentally battled with that voice and said how could God be there in the middle of a genocide? That is when she challenged herself: Did she really believe in God? Was her faith truly strong?

She believes God spoke to her and told her “I created you because I love you. I gave you guidance; I gave you the commandments.” Ilibagiza read Scripture, but when she stumbled upon “Love your enemies,” she had to close the page.

“I realized that I was in trouble. I might not go to that nice place of heaven because I did not forgive. How can you when everyone who looks like you is killed?”

She didn’t like the idea of forgiveness, but because she knew her faith was in trouble, she started praying the rosary dozens of times a day. It brought her peace, even as she would be consumed with anger.

“Fear was killing me as much as anger. And impatience,” she recalled. “I ended up saying the rosary all day. … But when I came to the part of the Our Father to forgive those who trespass against us, my voice would say, ‘You don’t mean it. You are lying to God. You know you are not saying the truth. You risk losing him.'”

So she would skipped that part of the prayer, until she realized she didn’t have to skip it.

“For the first time in my life, I learned how to surrender. You don’t have to figure out everything,” she said. “God said, ‘Give it to me,’ so I gave it to God, realizing I still didn’t know how to forgive.”

“He was handing me a formula. (Those performing the genocide) don’t get it. They don’t understand the consequences. They don’t get the pain they are causing you. … And you being like them doesn’t change anything,” Ilibagiza said. “The world was divided two parts — love and hate. My plan was one of revenge, but the side of love offers peace. They forgive. They defend the truth and love. They defend peace. These are people I wanted to be with. … I knew I would spend my life praying for people on side of hate. Pray for them so that the grace of God would touch their heart. So, they too could change.”

But reality still tested her resolve and faith. When she exited the bathroom after three months, she weighed 65 pounds and discovered that among the millions of dead was her family.

“I put rosary down and cried. Then it was as if I felt a giant hand of God. His voice said, ‘Hey the journey of loved ones are done, but your journey is not over yet.”

Her choice was love or hate. She heard God tell her, “If you choose love or kindness, I will be with you. Whatever you need, I will give it to you.”

“For (the) first time, I felt the breeze on my face, and the warmth of sun. All those things I took for granted, but had never been thankful for. I felt free to talk,” she recalled.

While in a refugee camp, she turned to care for others. Even though she looked like a skeleton, she showed mercy, love and forgiveness.

“Take every moment as a gift. To this day, I take it as a gift. A day for new prayers, new intentions,” she said. “I have to be that loving person every day. I fall many times, and every time I do, I go to confession or get on my knees, confess and start again. … Hold on to God, no matter what is coming. Focus on prayer. Read the Bible and go to Mass. If I can forgive, anyone can forgive. I know the pain and damage of unforgiveness. There is so much joy. So much freedom in forgiveness.”