MURRELLS INLET, S.C. (CNS) — When the last days of August roll around every year, that’s when the memories start to return to Thomas Damore.

No matter the weather, no matter what he’s doing, they come back. Even though 20 years have passed and the retired captain of the New York Fire Department now lives hundreds of miles from the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11.

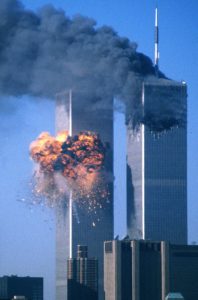

In his mind, he goes back to a day when fire, smoke, debris and death rained from a blindingly clear blue sky over New York City and back to the 50 days he spent climbing over piles of twisted metal where fires still burned, pushing aside piles of concrete and other debris, searching, always searching for anything left of thousands of people who perished in an instant at ground zero.

“Most of the year I don’t think too much about it, but beginning at the end of August, I can’t help but think back to that time,” Damore recalled recently.

“I can still hear the machines that were working to dig out all the debris. I can still smell the burning debris and when we were getting close to a body, you would get the smell of decay. I conjure that up too. Sometimes it doesn’t seem like it was 20 years ago. Sometimes it seems like a thousand.”

Damore is a parishioner at St. Michael Church in Murrells Inlet, about 15 miles south of Myrtle Beach, where he enjoys a game of golf, or a walk on the beach with his wife Veronica.

Although his life has completely changed from what it was 20 years ago, he will never forget where he was on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001.

Back then, Damore was part of Engine Company 48 in the Bronx. He was off duty that morning and didn’t realize what had happened miles away in lower Manhattan until a fellow firefighter called him with the news and quipped, “I’ll bet you’re glad you’re not working today.”

But Damore immediately knew he had to get to the scene.

He and six other men from his engine company joined about 30 other firefighters who got their equipment, commandeered a city bus and headed for lower Manhattan. Both towers had fallen by the time they got there around 11 a.m.

“At the time, it was total pandemonium with people running every which way,” Damore said. He said they reported to a fire chief in charge and got the assignment to do search and rescue. He said he directed his men to look anywhere they could for any sign of life, which they did for the next eight hours.”

They explored every open space, every void in the smoldering wreckage where it might be possible for survivors to be but found no one.

From that day forward, Damore split his time between regular shifts at his Bronx station and working at ground zero. He didn’t get home to his family in Queens until eight days after the terrorist attack.

Hope of finding survivors dwindled quickly after 9/11 and Damore and his fellow workers realized they were part of a long-haul recovery operation.

“Even when we did have a recovery, it was rarely a complete body,” Damore said. “Sometimes it was just a hand, a foot, a finger or toe. I tried to get my men to realize any recovery we made was going to be significant to the families. When we did find somebody, it became almost a joyous occasion because we knew that someone was going to be able to get some closure.”

Whenever someone was found, all work at the site would stop, he said. The person was placed in a stretcher, covered with an American flag, and carried to a waiting ambulance.

Damore said faith helped sustain the workers during their grim tasks. Fire department chaplains were constantly present and he and others frequently walked to a nearby church where volunteers offered food and there was a daily noon Mass.

He worked his shifts at ground zero until Feb. 6, 2002. On his last day there, his team recovered the remains of the son of his former battalion chief which he said was “a fitting emotional end for my time down there.”

Once that service ended, Damore went back to full-time work in the Bronx for a few more months and then retired in December 2002. He moved with his family to South Carolina in 2006.

Damore takes part in annual 9/11 memorial ceremonies at St. Michael Church and brings along the battered fire helmet he wore while working at ground zero.

Since both of his daughters were born after 2001, Damore said he knew how important it was to pass on the story of what happened that day to younger generations. He said telling the story is even more important 20 years on, and he stresses the importance of remembering how good overcame the evil that brought on 9/11.

That good, he said, was evident in the support he and his fellow first responders saw from their fellow New Yorkers — and from people around the country — as the nation came together in grief.

He said he still spends a lot of time in prayer for the firefighters he knew who died on 9/11, for all the other souls lost that day and for the ground zero workers who are sick because of the toxic debris they were exposed to day after day.

“I didn’t get sick; I’m one of the lucky ones,” he said.

“Because of all the people we lost on 9/11 and those who have died since, we can’t let people forget what happened. We still have people to this day who try to claim it was all a hoax, so we have to keep teaching the history. We simply can’t let people forget.”