By Rhina Guidos, Catholic News Service

In a stretch of land known as Las Aradas, in a remote part of northern El Salvador bordering Honduras, Salvadoran Cardinal Gregorio Rosa Chavez blessed the monument, sprinkling holy water on top of the bricks bearing the names of those in the mass grave underneath.

On May 14, the 42nd anniversary of the Sumpul River massacre, named for the nearby river, he praised the survivors and descendants of those who were killed there for “purifying the memory” of what happened to their loved ones by being present at the commemoration.

More than four decades after the massacre, bodies are still being recovered, and local Catholics use the commemoration as an opportunity to teach and practice a core teaching in Christianity: forgiveness.

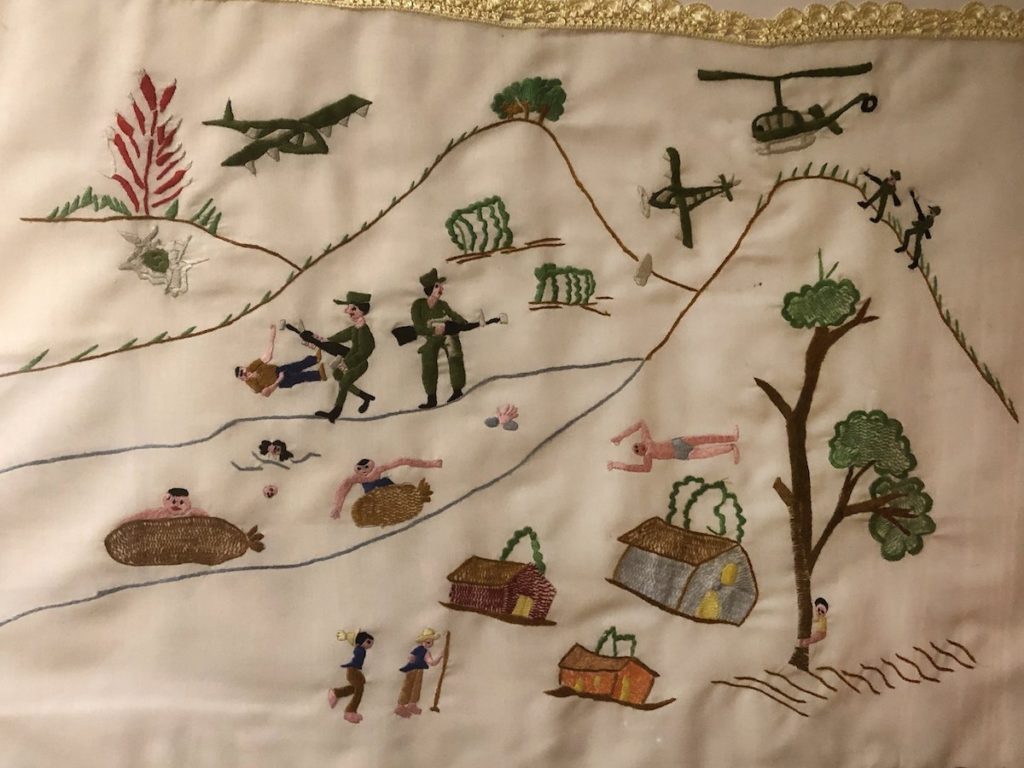

Survivors of that day say hundreds of armed soldiers on the Salvadoran side of the river began invading towns around the Sumpul (pronounced soom-pool), driving terrified residents, suspected of being leftist sympathizers, toward a demilitarized zone on the riverbank, where locals typically sought refuge.

But instead of refuge, they found death and horror. Surrounded by Salvadoran soldiers on one side and Honduran soldiers on the other, they began running. Some drowned, others were stabbed with bayonets, and some were shot by soldiers attacking from a helicopter above. In the mayhem, a few escaped.

The government closed off the area and denied the attack, but witnesses, including a Capuchin priest from the U.S. who helped survivors on the Honduran side, testified that he saw what remained of the carnage. He told The New York Times in 1981 that “there were so many vultures picking at the bodies in the water that it looked like a black carpet.”

Remains have been found in various mass graves nearby over the years, though many bodies were suspected to have been carried by the current or crudely scattered elsewhere by soldiers. On April 30, remains of six victims from the massacre, found in a pit discovered last year, were laid to rest following a Catholic funeral Mass.

“This proves that this did happen and it’s not a lie, as many others have said,” María Mejía, a survivor of the massacre, told the newspaper El Diario de Hoy after receiving the remains of her father and two uncles more than four decades after they were killed.

“They say there are two conditions for peace, which have been denied to us in El Salvador: truth and justice,” Cardinal Rosa Chavez told the crowd of about 500 who attended the recent commemoration in Las Aradas. “But there’s a third one. To walk toward the future (after tragedy), we must purify the memory, which means not being tied to the past.”

That doesn’t mean burying the truth, forgetting what has happened, but looking at the truth, and — through the Gospel — forgive as Christ instructed, he said.

If not, hate and vengeance take over, he said, hinting that it’s precisely what’s taking place in El Salvador today. The government, in mass detentions it says it is carrying out to rid the country of gangs, also has detained innocent people. More than 30,000 have been detained since late March, according to authorities, and the president said that while errors are bound to be made, they are minimal, “1%.” Due process and other rights have been suspended, and other countries, including the U.S., have raised alarm at the violations.

But many in El Salvador, the cardinal said, “are happy about it” and say they are finally at peace. They say they don’t have pay extortions anymore and are not being terrorized by gang members who are now on the run. They even wish for the death penalty for those who are detained, regardless of whether they are guilty of a crime.

“What we are seeing is a mirage,” Cardinal Rosa Chavez said. “That is not how you build peace.”

The cardinal, who is the auxiliary bishop of the Archdiocese of San Salvador, was criticized by a Salvadoran politician from the ruling party for his comments, calling the prelate a “mercenary of religion” and said he was responsible “for so much damage.”

The cardinal said that he, and the country, could learn a lot from those who gathered at the massacre site, who have not forgotten, but learned “to purify the memory” of what happened to their loved ones.

“That means to make our hearts heal, from rancor, from resentment and hate. Hate destroys from inside. Hate doesn’t edify. That’s what Jesus talked about in the Gospel today,” he said referring to the Gospel reading from the book of St. John, which says: “This I command you: Love one another.”

For the past 10 years, survivors and their supporters have planted trees at the site, gathered there to share food and music, to pray and reflect, to celebrate the Eucharist, and, little by little, have added monuments, including one of St. Oscar Romero, which the cardinal blessed. Organizers also have added skits illustrating what happened during the massacre, including messages of forgiveness and peace to educate the pilgrims.

One of them this year was Felipe de Jesus Abrego, who wasn’t born when the massacre took place, but walked almost two hours to the remote site this year to learn about history.

“What remains with me from that day is (the cardinal’s) main message. He told us not to let anyone stop us from our dreams (of peace), to live without hate,” Abrego told Catholic News Service.

The cardinal said he was particularly happy to see young Salvadorans like Abrego at the event, and their interaction with elders, including those who could tell them about the past, illustrating what Pope Francis has said: that old and young must walk together on the journey of salvation.

“I came here to see the future with hope,” the cardinal said. “I leave having learned lessons this morning. This shows me how our country can be transformed … in the capital we’re intoxicated with words that are untrue, words of regret, rancor, condemnation. Coming here is like breathing oxygen, seeing young people who believe in what happened in the past and seeing it as a challenge to the future, to fight so that things are not forgotten and remain in impunity.”